Lesson Template

Part 1 - Using Pre-writing Strategies

- Lesson title: Using Pre-writing Strategies

- Student-friendly summary of lesson: You will learn how to anticipate questions that readers might ask about your topic, prioritize your ideas, and write an outline.

- At least 3-5 key words in the lesson, including their definitions from the TEKS Glossary:

Key Word |

TEKS Glossary Definition |

|---|---|

| Thesis | A statement or premise supported by arguments. |

| Outline | A short verbal sketch that shows in skeleton form the pattern of ideas in text or in a draft prepared for speaking or writing, often with main and subideas highlighted by numbers and letters.

|

| reader-friendly writing | Writing in which the author, viewing a composition as a communication with others, is attentive to the needs of the reader; prose writing that reflects the efforts of authors in preparing and revising texts to take into consideration the background, needs, and interests of an anticipated audience; reader-based writing. Note: Writing that fails to reflect a sense of audience is considered reader-unfriendly writing or writer-based writing.

|

| Brainstorming | A technique in which many ideas are generated quickly and without judgment or evaluation in order to solve a problem, clarify a concept, or inspire creative thinking. Brainstorming may be done in a classroom, small group, or individually.

|

| logical order | How a writer organizes text when building an argument. The writer presents ideas or information in a sequence that makes sense to him or her and addresses the audience’s needs. |

| argumentative essay | An essay in which the writer develops or debates a topic using logic and persuasion. |

| parallel structure | A rhetorical device in which the same grammatical structure is used within a sentence or paragraph to show that two or more ideas have equal importance.

|

Introduction

Image ©2007, PetteriO

Image ©2007, PetteriO Put yourself in this situation: You have a writing assignment. You have chosen your topic. You have a thesis in mind. You have done some brainstorming about support for your thesis. What’s next?

Start writing? Maybe so, but probably not.

Hold off on starting a draft and instead plan some more. The best thing to do at this point (with your thesis and brainstorming material in hand) is to make a working outline.

This is not going to be a formal outline with many levels of subordination (headings and subheadings); it will only indicate the main divisions of your paper and subdivisions of the body.

There are at least two reasons to create a working outline at this point:

- It will make the paper easier to write. By knowing how the essay will hold together, you can write each part and feel confident that what you are writing is going to fit into the larger organization of the paper. In other words, you will be able to focus on separate, shorter sections one at a time.

- It will make your paper more reader-friendly. Your finished product will have a clear structure, and that means it will be easier for a reader to follow. It will also be more focused; you are less likely to wander off into a digression. This is helpful to a reader who wants a clear presentation of what your proposal is and what your reasons are for making it.

The outline we will make is just intended to help you write the first draft of the paper. At the first-draft stage, you may want to change things as you revise or as you are writing. Even your thesis may change. You do not want to commit yourself to a detailed plan that will discourage changes during the drafting process. A formal outline is best completed after the first draft and, at that point, can serve as a check of the logic, coherence, and unity of the whole paper.

Sorting Support

You should have done some brainstorming, freewriting, clustering, or another idea-generating activity to collect possible content for your essay, but all this possible content and all of these ideas for supporting your working thesis are in a jumble. What do you do to get organized?

Before you write your working outline, you need to have both a position on the topic (a working thesis) and some reasons for a reader to agree with your thesis (possible support). Only then should you decide how to put the parts together in an essay.

Let’s do a little getting-to-know-you activity to be sure we are clear on what’s what in all that raw material. Topics, theses, and support: these are the parts we are going to need. From the phrases below, decide which are topics, which are theses, and which are supporting reasons. Click on the word you think is correct to see whether you have chosen correctly.

Working Thesis: Dog owners should be tolerant of dogs’ occasionally annoying, dog-like behavior (shedding, drooling, scratching, tracking mud in, having burrs, etc.).

Reasons for supporting this thesis:

- Dogs can’t understand human language.

- Dogs aren’t in control of some things (like opening doors to go outside).

- Dogs are helplessly interested in other animals.

- Dogs can protect us.

- Dogs like to chase things.

- Dogs get bored.

- Dogs deserve something for all they give us.

- Dogs have to put up with us.

- Dogs can be taught well only through training.

How can the writer bring order to this jumble? Can you see how any of these could be grouped together? Using your Take Notes Tool, answer the following questions to begin bringing order out of the chaos. When you’re finished, check your understanding.

- Which 2 ideas, aside from the first one, are about what dogs can’t do?

- Which 2 ideas are about dogs' natural instincts like idea 3?

- Which 2 ideas are about dog-to-human relationships and could be grouped with number 4?

- Ideas 2 and 9 are both like the first one and could be grouped with it. (Idea 9 is about a limitation on how dogs learn.)

- 5 and 6 are both about natural instincts.

- 7 and 8 are about dogs’ relationships with humans.

Close

There are probably other ways to group these ideas, but for now let’s work with the groupings below. The next step will be for the writer to give each one a label.

Dogs can’t understand human language.

Dogs aren’t in control of some things, like opening doors to go outside.

Dogs can be taught well only through training.

Dogs are helplessly interested in other animals.

Dogs like to chase things.

Dogs get bored.

Dogs can protect us.

Dogs deserve something for all they give to us.

Dogs have to put up with us.

We not only want labels for these categories; we also want the labels to have a parallel structure.

The labels should be constructed in the same way. Below are label examples that do not have parallel structure:

Dogs can’t do some things.

Having a dog has its rewards.

Natural instincts are always going to be part of dog behavior.

These three statements express the ideas we want to include, but the way they are constructed doesn’t match. It is much easier to think of the three ideas as a set if we express them in a grammatically parallel way. The easiest way to go about writing for parallel structure is to start each label with the same words. Using your Take Notes Tool, rewrite the labels above so that they all begin with “Dogs have...”

- Dogs have limitations.

- Dogs have relationships with humans and deserve credit for it.

- Dogs have natural instincts.

Close

Remember that sorting out the support as we’ve done here involves two steps:

- Grouping the support into categories

- Giving parallel labels to the categories

Of course, you might also want to just get rid of some ideas if they seem irrelevant or repetitive.

A Working Outline

Photo by: Ellen Levy Finch

You want an outline that will work for you as you write a first draft of the essay. You do not need more than a couple of levels of subordination. But you will include an introduction and a conclusion along with the support for the thesis in the body of the essay.

The introduction should start the reader thinking about the topic before the thesis is presented. In the case of the essay on dog tolerance, the introduction might start with a story about a dog owner who was constantly frustrated by her dog’s behavior even though it was behavior that anyone would expect from a normal dog. Or you might start with a series of questions: Do people expect too much of their pets? Do they expect owning a dog to be frustration-free? How much of what annoys people about their pets is normal animal behavior? Do dog owners get angry about a dog just being a dog? An introduction should introduce the topic, get readers thinking about their relationship to the topic, and then present the thesis.

The introduction should:

- bring up the topic.

- get the reader thinking about the topic.

- present the thesis.

The conclusion should restate the thesis and the main supporting reasons, although not in exactly the same words as the introduction. But the conclusion is also an opportunity to recommend some action (for example, Dog owners should take a dog-training class to help them better understand what it is reasonable to expect). Or, you may reintroduce something mentioned in the introduction, like a reference to the story of the frustrated pet owner.

The conclusion should:

- refer to the introduction

Do one or both of the following:

- recommend action

- restate the thesis

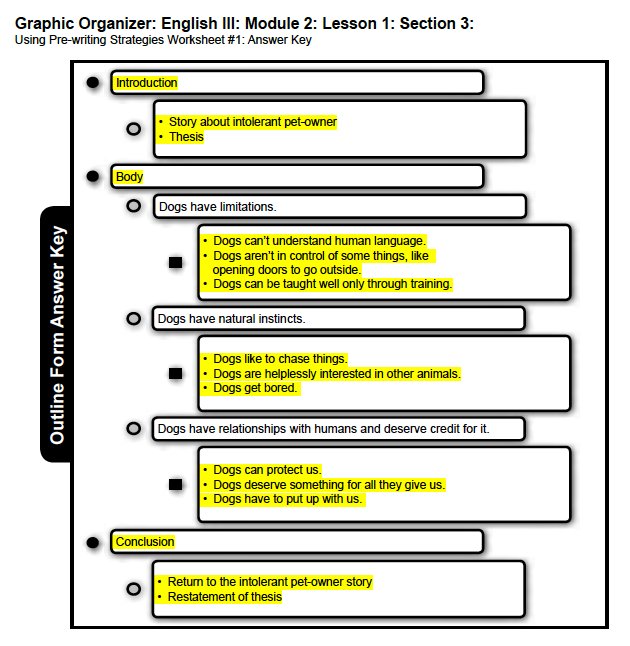

Next we’ll put our outline in order by using a graphic organizer. You can type into the graphic organizer and/or download and print it.

Prioritizing the Items in an Outline

Are we finished? Almost, but not quite. Right now the order of the outline items follows the order in which we thought of them. If we leave them in this order, it’s likely that the eventual essay will be writer-based rather than reader-friendly. We want to put both the category labels and the supporting points in a logical order that will emphasize the strongest ideas. That means putting them last. What is placed at the end of a series is most likely to be remembered. It is usually assumed that the author places the most important item at the end.

We will want to start with what seems the most obvious or least surprising idea, and end with what is the most remarkable or dramatic idea. Let's revisit the outline from the previous section.

Below are questions to help you think about organizing the sections. Answer them using your Take Notes Tool, and check your understanding about each question.

You’ll begin by taking major items—introduction, body, and conclusion—one at a time:

- Introduction: Is there any prioritizing to do here? What is the most important element in the introduction? Is it the final item?

- The thesis is most important and should come last.

- Which is the most obvious reason that we should be tolerant of dog behavior?

- Dogs’ natural instincts are the most obvious of the three reasons. This should come first.

- Which is the least obvious idea about dog tolerance? That is, which idea needs to be placed in the most important position?

- Dogs deserving credit will need the most involved argument. In this sense, it is the most unusual of the supporting details. If the writer is going to treat it this way, it should come last.

This leaves the “limitations” idea for the middle position.

- Dogs deserving credit will need the most involved argument. In this sense, it is the most unusual of the supporting details. If the writer is going to treat it this way, it should come last.

- Not much to consider here. What is the item of crucial importance in the conclusion?

- The thesis should be the final item.

Now let’s decide how the points of each subsection should be ordered:

- Support for “limitations”: How would you arrange the three examples of limitations? In this case it may be possible to combine two.

- The idea that dogs need training is connected to the idea that dogs do not understand human language, so these two might be discussed together—probably after the other item. Dogs’ lack of control over such things as going outdoors is probably the most obvious example and should be first.

- Support for “natural instincts”: There may not be a very surprising item in this category, but two of these ideas are closely related.

- Interest in other animals and chasing things are more closely related to each other than being bored is to either of them. Boredom should be the third item.

- Support for “relationship”: One item is an example of another. Those two should go together. But should they come before the third item or after it?

- Protection is an example of the things dogs give us. These two should be first because the other item, about dogs having to put up with us, is stated in a humorous way (although it is a valid point). The joke-like item should be positioned at the end, like a punch line.

Use the next graphic organizer to finish the working outline. Follow the directions found at the top of the page. As you work, pay attention to the points that have been prearranged in their boxes to agree with the discussion above. You can type into the graphic organizer or download and print it and handwrite your answers.

As a reminder, here are the steps you took to construct the working outline:

- Group the support into categories

- Give parallel labels to the categories

- Add the major sections: introduction, body, and conclusion

- Fill in the body with labels for categories

- Fill in the support/reasoning for each subsection

- Prioritize both the category labels and the support

Try It Out

The final activity in this lesson is to group, label, and arrange items into a working outline. The thesis is given below along with a list of supporting reasons. Using your Take Notes Tool, make a working outline that makes sense to you. Consider making two groups of supporting reasons instead of three. Include a place for the introduction and conclusion.

Thesis: Drivers should be tolerant of what looks like “bad driving” by other drivers.

Brainstormed ideas:

- There may be an explanation for the supposed bad driving that excuses the driver, such as swerving to avoid a hazard in the road.

- Student drivers have to be given some understanding.

- Intolerant reactions such as honking, tailgating, and making vulgar gestures do not make bad drivers into good drivers.

- Drivers who are simply being cautious can be mistaken for bad drivers.

- Being intolerant on the road can make you a bad driver.

- Intolerant reactions such as honking, tailgating, and making vulgar gestures can cause accidents.

- Intolerant reactions such as honking, tailgating, and making vulgar gestures can make bad drivers into much worse drivers by making them nervous and distracted.

- Drivers who are new to an area may need to look at street address numbers or other location signs as they drive.

Using a final graphic organizer, group, label, and prioritize the ideas. You can type into the graphic organizer or download and print it and handwrite the answers.