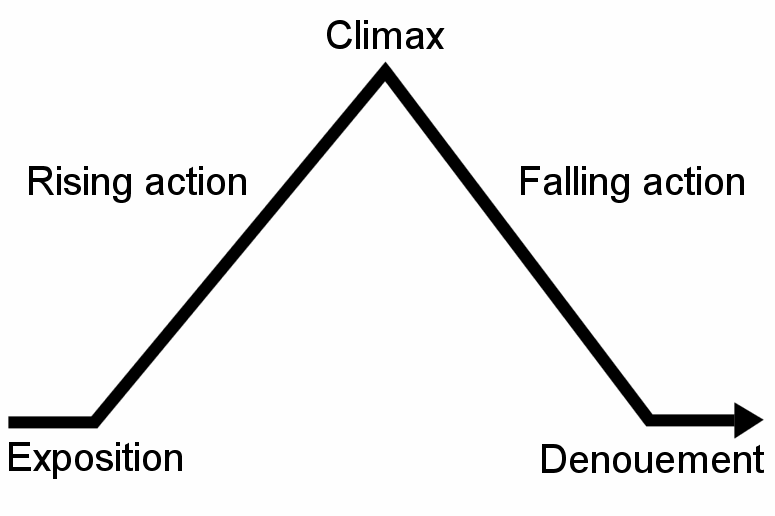

Plot is a series of related events, each event connected to the next, like links in a chain. The trick in literary text is to leave some unanswered questions: intrigue the readers and give them a reason to continue reading. We are moved from one line to the next by the plot. In a sense, each event in the plot is designed to hook our curiosity and pull us forward to the next event. Many short story stories, including “The Boys,” follow a time-honored path of rising action to climax to falling action.

Freytag’s pyramid is a chart of the escalating actions that make up the average plot. The line rises to a point as tension builds and slopes downward as the tension subsides.

Source: Freytags Pyramid, Wikimedia

The typical plot is divided into five main elements: exposition, rising action, climax (the turning point), falling action, and resolution (or denouement).

1. Exposition is the beginning of the story, or the situation before the action starts. The writer creates the conditions that are present at the beginning of the story and describes the setting. The writer establishes the main characters with their positions, circumstances, and relationships to one another and introduces the exciting force or initial conflict. Sometimes called the narrative hook, this initial conflict will continue throughout the story.

Chekhov describes a joyful reunion at Christmas time, but from the beginning, the shadowy Lentilov alters the mood in the household.

Source: Neapolitan boys fishermen. After Fishing, Orest Adamovich

Kiprenskii (1778-1836), Wikimedia

2. Rising action is the series of events, conflicts, and crises in the story that leads up to the climax, providing progressive intensity that complicates the conflict.

Lentilov plots with Volodya to run away to America where the two of them will fight American tigers and will plunder to stay alive. Although Lentilov appears as fearless as his imaginary name, “Montehomo, the Hawk's Claw, Chief of the Ever Victorious,” Volodya is so conflicted that he begins to cry. The younger sisters become aware of the plan to flee to America but are powerless to interfere.

Now, open or return to the PDF of “The Boys” and read Part 3, the end of Chekhov’s story.

3. Climax is the turning point of the story. A crucial event takes place at the climax, and the plot moves toward its inevitable end.

The question that kept us reading in the rising action section of the story was “Will Volodya embark on this outrageous adventure with Lentilov?” Once we discover that the boys are gone, we read on with new unanswered questions. While we know it’s unlikely that the boys have crossed the Bering Strait, we are curious how far they got. Now, like Volodya’s family, we want to know if they are safe.

Source: ??

4. Falling Action is all of the action after the climax. The main character may encounter more conflicts in this part of the story, but the end is inevitable.

The family waits for the juvenile explorers with the same anticipation we witnessed in the beginning of the story. Chekhov masterfully repeats the opening details. Again, the boys arrive in “a sledge pulled by three white horses in a cloud of steam.” Again, they are met with the identical exclamations.

“Volodya's come,” someone shouted in the yard.

“Master Volodya's here!” bawled Natalya.

This homecoming is more meaningful to the readers, however, because we have identified with Chekhov’s main character and become invested in his outcome. We have experienced Volodya’s turmoil and realized that his safety was in doubt. Our knowledge about Volodya is why this second welcome makes a greater impression upon us.

5. Resolution, or denouement, is the tying-up of the loose ends and all the threads in the story.

Chekhov commented, “When I am finished with my characters, I like to return them to life.” We know that a lecture and scolding is in the boys’ future. We can also guess that Lentilov will not be welcome to return on the next school holiday. If Chekhov had wanted to teach a moral, he might have written the story with Lentilov repenting, but instead, he allowed Lentilov’s character to remain a fearless adventurer to the end.

Source: Story Road, umjanedoan, Flickr

As you think about the story of your visitor or visit, you may want to plan the major events that will occur. If you do so, follow the universal pattern of Freytag’s pyramid. Create events that give your story a clear beginning, middle, and end. You might also consider the following questions as you think about the plot of your story:

- Has the conflict been carefully established in the rising action?

- What is the climax of your story?

- What is the setting?

- Will the resolution leave your readers satisfied?