Making Connections

Source: 90/365: A short history., Adam Franco, Flickr

Reading historical documents or historical literature can be difficult. You have the disadvantage of not living in the time when the text was written, and you may not understand the nuances surrounding events of the era. Sometimes you can find background information from within the text itself. Other times, a quick search on the Internet can fill in the gaps.

Another way to make sense of the past is to use a strategy that connects the reading to things you know. This strategy is called “Text-to-Self, Text-to-Text, Text-to-World.” It involves

- reading, making notes, and connecting unfamiliar words and ideas to knowledge you may already have about the topic;

- connecting the topic to other texts that may be similar to what you’re reading; and

- connecting the topic to current events and the world around you.

You should begin by annotating the text, noting anything that strikes you as familiar. Does this text sound like something you’ve read or heard before? Are there words that you think you know, but you’re not quite sure? What things do you not understand? Note these things so that you can continue to think about them.

Even though the events in what you’re reading may have taken place long ago, do they sound like they could be taking place today? Make notes about the similarities and differences. The more notes you make about the text, the easier it will be to make comparisons to modern day texts and events.

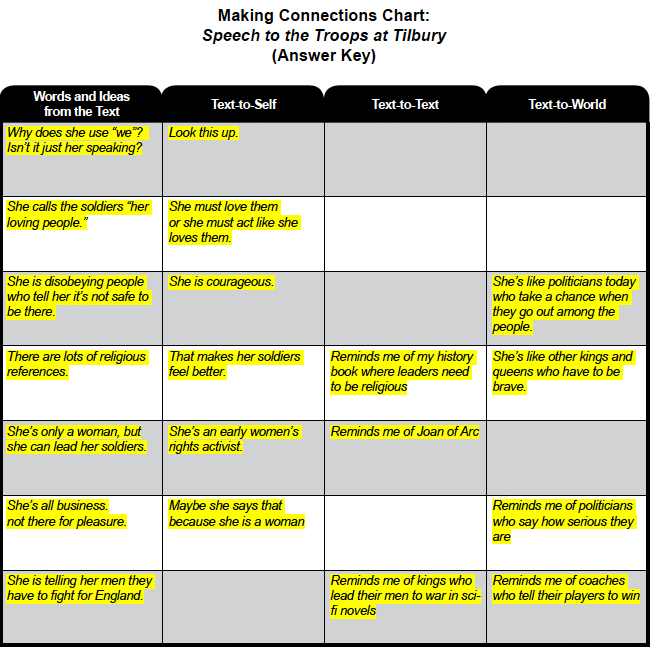

You can practice the strategy using the graphic organizer, which you can download and print. Next, read the following short speech Queen Elizabeth I gave to her troops in 1588 at Tilbury. Use your graphic organizer to make notes about the speech as you read. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see other possible responses. Graphic Organizer Instructions

Source: Painting of Queen Elizabeth, Project Gutenberg

Here’s some background before you read.

The “Speech to the Troops at Tilbury” was delivered on August 19, 1588, by Queen Elizabeth I of England to the land forces assembled at Tilbury. The Spanish Armada had been driven from the Strait of Dover eleven days earlier, but troops were still held at the ready in case the Spanish army of Alexander Farnese, the Duke of Parma, attempted to invade from Dunkirk; two days later the Queen’s army was discharged.

On the day of the speech, the Queen left her bodyguard at the fort at Tilbury and rode among her subjects. She was escorted by three people: Lord Ormond who bore the Sword of State, a page who led the Queen’s charger, and another page who carried her silver helmet on a cushion. The Queen, mounted on a grey gelding, followed the two pages. She wore white with a silver cuirass. Her Lieutenant General, the Earl of Leicester, followed her on the right, and her Master of the Horse, the Earl of Essex, followed her on the left.

Speech to the Troops at Tilbury1

My loving people

We have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit our selves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear, I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good-will of my subjects; and therefore I am come amongst you, as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all; to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field. I know already, for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns; and We do assure you in the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. In the mean time, my lieutenant general2 shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over those enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people.

1. Delivered by Elizabeth to the land forces assembled at Tilbury (Essex)

to repel the anticipated invasion of the Spanish Armada, 1588.

2. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester; he was the queen’s favorite.

Download a pdf of this chart.

Download a pdf of this chart.Probably the most difficult thing about this passage is Elizabeth’s use of the royal “we.” If you didn’t know that kings and queens often refer to themselves using the plural “we” rather than “I,” then this could be confusing. So how did you tackle this issue as you read? You should have noted it the first couple of times that it occurred in the text. Then, if you couldn’t make a connection that helped you understand this particular point, you could have asked a teacher or another student, or you could have gone to the Internet for help. If you didn’t understand how “we” is used in the speech, would it be an obstacle to your understanding of the piece as a whole? Probably not, so don’t be discouraged and give up if you come across something in the text that’s not easy to understand. Keep going; when you reach the end, see if you understand the text overall.

Now that you’ve made notes on the worksheet and thought about how to tackle this document, think about what you’ve learned. For example, what insights have you gained about Queen Elizabeth I? Take a minute and write two or three sentences using your notes about what you’ve learned from reading her speech. When you’re finished, check your understanding to compare your response.

Sample Response:

Many of Elizabeth I’s ideas don’t seem all that old fashioned. She talks about having God on her side; she worries that because she is a woman, she will not be as strong a leader; she worries about the loyalty of her troops; and finally she becomes the coach of the team, exhorting her men to victory. This speech was written almost 500 years ago, but it only requires a little patience to see that Elizabeth is very similar to some of our leaders in government. She is also very much like our generals who speak to their troops to get them to focus on winning a battle.

CloseNext let’s discuss another strategy that will help when you’re faced with difficult reading.