Source: student in thought, kyle stauffer, Flickr

Say you are thinking of writing a story for which you already have your plot and setting. Now it’s time to design the right characters. How do you go about it? Now that you know a little about the two types of characters usually found in stories, you can take the next step: Decide which characters would best tell the story you want to tell. How do you choose your characters?

As is often the case when you begin a creative project, it’s best to start with what you know. For example, if you want your plot to involve a young boy who has a special gift such as a serious athletic ability, consider using a model to help with your characterization. Think about people you know. Do you know a young boy in real life who has a special gift? If so, you may be able to base your fictional character on him. If no one matches the role to your satisfaction, enlarge your search to include people whom you may not have met. Real people you have only read or heard about can make good models for characters. If you think of someone who will help with the creation of your character, you can interview or simply analyze the person as you try to figure out personal attributes you wish to use for your own character.

Source: Water everywhere, Steven Polunsky, Wikimedia

A helpful way to familiarize yourself with your character is to take a few minutes to write down some personality traits or characteristics that might work in the story. You can simply fold a piece of paper in half and make a T-chart (a chart with two columns). One side could be for the positive aspects of your character, the other for the negative aspects.

Try it now. Use your notes to create a chart with a character you have in mind. After you’re finished, try this: Write a journal entry from the point of view of the character who has the traits on your T-chart. When you are finished with the chart and journal entry, check your understanding to view a possible response.

Try it now. Use your notes to create a chart with a character you have in mind. After you’re finished, try this: Write a journal entry from the point of view of the character who has the traits on your T-chart. When you are finished with the chart and journal entry, check your understanding to view a possible response. Sample Responses:

| What’s good about this character? | What’s not good about this character? | |

| Generous | Never has any money because he gives it all away | |

| Outgoing | Really hard to make plans with because always busy | |

| Talented soccer player | Can come across as a little arrogant at times | |

| Always late for practice |

Sample response for journal entry as written by new character:

| Well, here it is Saturday, and five people have called and asked me to hang out with them. The other day, I loaned Robin lunch money, and she said she wanted to be part of our group tonight, but then she never called back, not that I care that much. I’m late for soccer practice—as usual. I’m supposed to meet the team down at the park . . . like 20 minutes ago. They’ll wait. Hahaha. |

Now, do you remember the mnemonic STEAL? Let’s think about each of those elements more thoroughly. Watch this short video to also get some ideas about how to develop your characters.

Speech (S)

Source: The Man Who Speaks Many Languages -Andre14, Ema Chen, Flickr

Having a character talk to others is an efficient way to develop a character because it is what we do in everyday life. We have conversations of all types with all manner of people: academic discussions with teachers and classmates, business conversations with colleagues, and personal talks with family and friends—or sometimes even foes.

An author uses dialogue to move the action along in a story and show how characters react to conflict. The conflict may be internal or external. We (the readers) can learn a lot about characters from what they say to others or themselves, just as we can learn about the people around us in everyday life by paying attention to their speech. In fact, how a character says something is often as important as what the character says.

Source: Marshall, Henrietta Elizabeth (1908), Wikimedia commons

“Ben,” said Ben’s mother, “what kind of activities did you take part in while at school today?”

“I had an entire day of activities, Mother. What kind of activity do you wish for me to tell you about?” he replied.

Source: mother and son, anndewig, Flickr

Does this conversation sound natural to you? If not, perhaps you are not used to hearing people speak so formally. What if the dialogue were part of a short story a British author wrote in the nineteenth century? What if people from that period did indeed talk like this?

By the way, did you notice the bit of irony in Ben’s voice? Does it seem as if he doubts his mother cares what he does at school? This would be another way for the author to develop the characters of Ben and his mother. The dialogue hints at a cold relationship between mother and son.

Now consider this dialogue:

“How was school?” said Ben’s mother, yelling over her shoulder on the way out of the room.

“I dunno,” he said, thinking of all the times she had forgotten about his big games. “The usual I guess, not that it would cut any mustard with you these days.”

Does this dialogue feel different to you? If so, how?

One of the things you probably notice right away is the author’s use of slang. Ben says “I dunno” instead of the more formal “I don’t know.” He also uses the figure of speech “cut any mustard” instead of “matter very much.” These are stylistic choices the author makes to help characterize Ben and his mother.

The author also lets us in on the thoughts, or internal monologue, of one of the characters. Ben is “thinking of all the times she [his mother] had forgotten about his big games.” Internal monologue is useful for giving readers added information about a character while at the same time allowing readers to make inferences and draw conclusions.

In this second example, the irony is still present, but how the author presents it—choosing a more conversational tone and a common figure of speech—leaves a different impression on the reader.

Thoughts (T)

Source: in thoughts, Thomas Lieser, Flickr

Often, writers develop a character by showing you the character’s thoughts. In that way, the reader can begin to get a fuller understanding of the character that goes beyond description and even dialogue. In the excerpt that follows, the main character Annie is down on her luck in a racially segregated society. Faced with few choices, she thinks about her future.

Annie, over six feet tall, big-boned, decided that she would not go to work as a domestic and leave her “precious babes” to anyone else’s care. There was no possibility of being hired at the town’s cotton gin or lumber mill, but maybe there was a way to make the two factories work for her. In her words, “I looked up the road I was going and back the way I come, and since I wasn’t satisfied, I decided to step off the road and cut me a new path.”

By showing us Annie’s thoughts, writer Maya Angelou in the short story “New Direction” depicts a believable, determined, and courageous woman.

Effects on Others (E)

Another method of indirect characterization is to write about the effect the character has on another character or a group of people. When one character reacts to another, the character’s personality is sometimes revealed, and the reader continues to gain insight into the character.

We couldn’t finish this section without looking at an excerpt from one of Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Read the following short segment, paying attention to the effect that one character, a minor character in some ways, has on another.

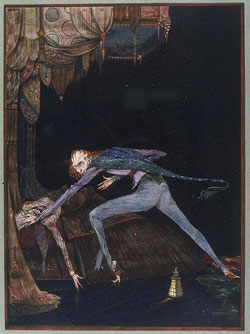

A painting depicting a scene from Poe’s “The Tell Tale Heart.” It shows a maniacal looking man choking an elderly who is man lying in a bed

It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain; but once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! Yes, it was this! He had the eye of a vulture—a pale blue eye, with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me, my blood ran cold; and so by degrees—very gradually—I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever.

Action (A)

Source: bsb 2012 : close action (51 vs 60)., Patrick Mayon, Flickr

Even though your stories are fictional, their success depends on your ability to make your readers comfortable enough with your characters to identify with them. You can do this by writing about characters doing realistic things in situations that you create. In addition to developing characters in the ways previously mentioned, another way that authors characterize the people in their stories is through the action that takes place.

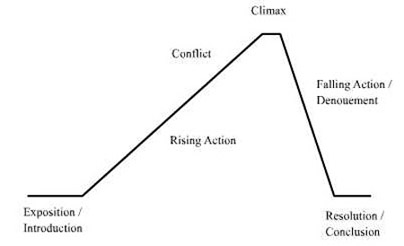

Source: Plot Diagram, Drew Davidson, Ph.D,

Plotting the Story and Interactivity in Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time.

Action includes anything that happens in the story that advances the plot; rising action brings the story to a climax, and falling action brings it to a resolution. Action can be an event or dialogue or a reaction to an event or dialogue. Authors typically use two different types of action in their stories, and both often involve some sort of conflict: (1) major events, including sudden plot twists and unexpected turns, and (2) common actions, including everyday gestures and physical movements that serve to carry characters from one scene to the next. Showing your character embroiled in a sudden confrontation with an angry mob, an evil sorcerer, or a defiant antagonist is definitely a major event. A scene showing your character having a calm conversation with a friend, or taking an uneventful walk to the post office might be considered minor. Both kinds of action show readers something about your character while moving the plot along.

Let’s look at how writer Isabelle Allende uses rather ordinary actions to describe the eccentric Uncle Marcos in the novel The House of the Spirits.

While the rest of the household tried to sleep, he dragged his suitcases up and down the halls, practiced making strange, high pitched sounds on savage instruments, and taught Spanish to a parrot whose native language was an Amazonian dialect. During the day he slept in a hammock that he had strung between two columns in the hall, wearing only the loincloth that put Severo in a terrible mood.

While these actions taken separately might be considered strange, putting them all together helps us picture the interesting character of Uncle Marcos.

Looks or Description (L)

Source: Cosplay character,

David Yu, Flickr

The most explicit way an author can develop a character—but maybe the least interesting—is by describing his or her physical attributes. Is your character short or tall, blonde or brunette? When it comes to fashion, does your character dress stylishly or casually? A character may be eager or merely efficient, fun or frustrating, joyful or jealous. A character may be manipulative or cooperative, rich or poor, pleasant or annoying. Below is an example of description from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone:

A giant of a man was standing in the doorway. His face was almost completely hidden by a long, shaggy mane of hair and a wild, tangled beard, but you could make out his eyes, glinting like black beetles under all the hair.

Although this is an explicit way to describe a character, it is often a good idea to limit the amount of this type of character development because too much description may bore the reader. There are other ways, less direct and perhaps more interesting, to bring a character to life.

Now you will have a chance to use some of these indirect characterization techniques. Using your notes, write a dialogue between two characters. Choose a scenario from the list below. Remember, this is fiction; what you write doesn’t have to be true, nor does it have to include people from real life. You can make a story line that is about anyone, anywhere, doing anything with anybody (within the limits of good taste, of course). In addition to dialogue and monologue, you can use the looks and description technique (described in this section) to make certain features of your characters more obvious.

Now you will have a chance to use some of these indirect characterization techniques. Using your notes, write a dialogue between two characters. Choose a scenario from the list below. Remember, this is fiction; what you write doesn’t have to be true, nor does it have to include people from real life. You can make a story line that is about anyone, anywhere, doing anything with anybody (within the limits of good taste, of course). In addition to dialogue and monologue, you can use the looks and description technique (described in this section) to make certain features of your characters more obvious.Below are some ideas for scenarios and characters to get you started. Choose one.

- Your character has a friend who wants to join a club at school. This friend, who tends to be a bully some of the time, wants your character to join as well and may even force the issue by having a conversation with your character after school. Write that conversation.

- Your character overhears a crime being planned while in the grocery store. He or she decides to have a conversation with someone else, hoping for help deciding whether or not to report it. This is the conversation you are to write. The person whom the character overheard in the store happens to be his or her best friend! Write the conversation between the character and the person the character goes to for advice.

- Your character accidentally sends a text message to the wrong person. The message contains information that could reflect badly on the character as well as the person who received the text message. Your character runs into this person by accident, and a conversation takes place. Write that conversation.

To make this exercise more interesting, consider finding a few friends with whom to share these dialogues. You could each choose a different scenario, or you could all respond to the same scenario and compare the dialogues you write. (Note: No response is provided because answers will vary.)

Now that you know about the two basic types of characters (round and flat) and the various ways to develop your own, let’s see how characterization works in several excerpts from Texas author O. Henry in the next section.