Source: Writer John, Onomatomedia, Wikimedia

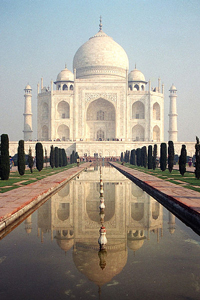

If you have ever heard a great speech, you may have experienced a physical reaction to it such as a quickening of your heartbeat. You experience this kind of reaction upon encountering a staggering masterpiece; you feel almost overwhelmed by a sense of beauty and grandeur. Imagine, for example, seeing one of the world’s great monuments, the Taj Mahal, in person.

Source: Taj Mahal 2002, Meutia Chaerani, Wikimedia

To experience the full force of the Taj Mahal’s impact, notice the way it shimmers in the sunlight, the beautiful symmetry of its dome on top of the cubic building structure, and the way that it appears to float above the pool in front of it. These design features ensure that it will move people for centuries to come.

Magnificent speeches work in much the same way: They make a lasting and powerful impression on people. How does someone create a magnificent speech, one that falls into the category of literary nonfiction?

The first thing the writer does is to go beyond the types of text structure normally found in nonfiction, such as cause and effect, description, or time order. Instead of using one of these organizational patterns, literary nonfiction is a narrative, meaning that it gives an account through carefully selected words that share the speaker’s message and set the tone. The writer may use anecdotes.

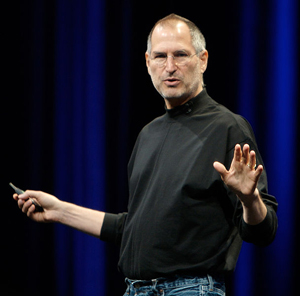

As you read the following passages from Steve Jobs’s commencement speech at Stanford University in 2005, pay attention to how he structures, or arranges, his speech. How does he present his ideas? How does this impact his message? Jobs was the cofounder of Apple Computer, Inc. along with Steve Wozniak, also known as “Woz.”

Commencement Speech at Stanford University

By Steve Jobs

Source: Steve Jobs WWDC07, Acaben, Wikimedia

Today I want to tell you three stories from my life. That’s it. No big deal. Just three stories. . . . And much of what I stumbled into by following my curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on. Let me give you one example. . . .

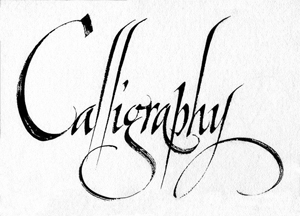

Reed College at that time offered perhaps the best calligraphy instruction in the country. Throughout the campus every poster, every label on every drawer was beautifully hand-calligraphed. Because I had dropped out and didn’t have to take the normal classes, I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and sans-serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating. . . .

None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But ten years later when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me, and we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography.

Of course it was impossible to connect the dots looking forward when I was in college, but it was very, very clear looking backwards 10 years later. Again, you can’t connect the dots looking forward. You can only connect them looking backwards, so you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future.

My second story is about love and loss. I was lucky. I found what I loved to do early in life. Woz and I started Apple in my parents’ garage when I was twenty. We worked hard and in ten years, Apple had grown from just the two of us in a garage into a $2 billion company with over 4,000 employees. . . . We’d just released our finest creation, the Macintosh, a year earlier, and I’d just turned thirty, and then I got fired.

I didn’t see it then, but it turned out that getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods in my life. During the next five years I started a company named NeXT, another company named Pixar. Pixar went on to create the world’s first computer-animated feature film, Toy Story, and is now the most successful animation studio in the world.

My third story is about death. When I was 17 I read a quote that went something like “If you live each day as if it was your last, someday you’ll most certainly be right. . . . ” It made an impression on me, and since then, for the past 33 years, I have looked in the mirror every morning and asked myself, “If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do today?” And whenever the answer has been “no” for too many days in a row, I know I need to change something.

Remembering that I’ll be dead soon is the most important thing I’ve ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life, because almost everything—all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure—these things . . . just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important. Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. There is no reason not to follow your heart.

Let’s consider the effect of the organizational structure Jobs uses in his speech. Jobs chose to include three anecdotal stories. In the exercise below, each sentence on the left provides text evidence that Jobs is beginning a new section of his speech. Drag and drop each sentence on the section it begins.

You may be wondering why he chose three stories instead of just one. You may want to figure out how he intended to connect all three stories into a larger meaning for the speech as a whole, creating lovely symmetry like we saw in the Taj Mahal. Beginning with his introductory paragraph, choose the words from the speech that best support the central idea of the speech. Click on the best choice. (Note: In the questions that follow, more than one answer may be correct.)

And much of what I stumbled into by following my curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on.

Source: Calligraphy bogdesko, AYS, Wikimedia

In looking at all these choices, you probably found that all four of the options seem to offer lead-ins to a point to be made, but only one offers the central idea:

“What I stumbled into by following my curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on.”

Now, determine how that central idea is illustrated in each of the three stories.

In his first story, Jobs describes how he took a class in calligraphy just by chance. Which statement provides the best text evidence to support this story’s connection to the central idea you identified above?

But ten years later when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me, and we designed it all into the Mac.

In other words, you might say that the central idea of the speech is that even though life events might happen unexpectedly or seem to be unimportant at the time, later they turn out to have been key turning points or critical steps on the way to the next life adventure.

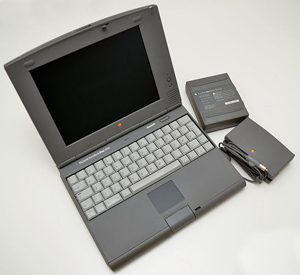

Source: Apple Macintosh Powerbook Duo 2300C, Photeka, Wikimedia

Now, look at a few bigger chunks of text evidence. Jobs’s second story, about getting fired from the very company he helped to establish, comprises two paragraphs in our excerpt from his speech. Which section of text evidence best helps us infer the connection to the central idea statement that “much of what [he] stumbled into by following [his] curiosity and intuition turned out to be priceless later on?”

We’d just released our finest creation, the Macintosh, a year earlier, and I’d just turned thirty, and then I got fired. I didn’t see it then, but it turned out that getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods in my life.

During the next five years I started a company named NeXT, [and] another company named Pixar. . . . Pixar went on to create the world’s first computer-animated feature film, Toy Story, and is now the most successful animation studio in the world.

Source: Toy Story, Unknown, Wikimedia

As we move on to the last story in the speech, you may initially wonder how the third section, which begins “My third story is about death,” relates to the central idea. How does a story about death fit in with “stories from my life”? Steve Jobs may have begun his last story with that statement to intrigue us into following his train of thought. Which of the following statements with text evidence helps you infer his overall meaning and the connection to the central idea of his speech?

Knowing and remembering that death is something that everyone eventually encounters helps us to let go of fear and pride, helping us focus only on what is “truly important.” This awareness allows us to “follow [our] heart[s]” and is therefore ultimately “priceless.”

Source: Nearsighted color fringing -9.5 diopter - Canon PowerShot A640 thru glasses - closeup detail, Dale Mahalko, Wikimedia

Each of these interpretations takes into account the meaning of the central idea statement: The unexpected can ultimately yield wonderful results. What a magnificent lesson that is. As we work on the masterpiece that is our own life, perhaps we should not fear a stray brushstroke or an unplanned color; it may eventually lead to something fabulous.