Source: Window View, thor_mark, Flickr

This section focuses on searching through the context of your reading for clues that will help you learn the meanings of unfamiliar words. Such words interrupt the flow of your reading in the same way that a bump in the road causes your parents to slow the car down.

Often writers will hint at a word’s meaning, getting you over the bump and enabling you to continue reading. Looking for context clues can help you see the hint. These clues can also help you learn new words and confirm the meaning of somewhat familiar words. Plus, you can use this vocabulary-building strategy by itself.

Using context clues involves making inferences, or educated guesses, about a word’s meaning by using definitions, examples, synonyms, antonyms, and other general kinds of clues in a text. After you infer something about a word from its context, you will be more conscious of that word and surprised at how often you see it. You may not be able to define it or use it in a sentence, but once a writer has brought a word to your attention, it can eventually become a word you know.

Source: Clue, pkohler, Flickr

Good writers like Frederick Douglass are considerate of you, the reader. They don’t want you to puzzle over the meaning of a word, get frustrated, or stop to use a dictionary. That’s why they include context clues or hints for challenging words. These hints come in various forms, but all are designed to help you figure out what an unfamiliar word means.

For example, using a relationship-to-other-words approach, you can figure out a general meaning for “peremptory,” a word from the section you are about to read. First, Douglass provides a context clue for this word in the form of a synonym. The conductor was “harsh in tone and peremptory” with the other passengers. Based on your knowledge of the word “harsh,” you infer that the conductor wasn’t friendly. Then you are given a context clue in the form of an antonym, “in friendly contrast.” So you might conclude that if the conductor starts acting “in a friendly manner” toward Douglass, his peremptory behavior toward the other passengers was “less than friendly.” He was, in fact, haughty.

Source: Time Traveling, diver227, Flickr

Now you are ready to apply what you know about looking inside a word at its morphemes, looking outside a word for context clues, or looking up a word if necessary. Read the conclusion to Douglass’s story about the memorable day when he escaped from slavery.

For this exercise, choose the word from each pull-down menu that seems to fit the surrounding context. When you’re finished, answer the questions that follow about other challenging words in this narrative. If you choose correctly from the menus below, a green border will appear around the word. If you choose incorrectly, a red border will appear.

For this exercise, choose the word from each pull-down menu that seems to fit the surrounding context. When you’re finished, answer the questions that follow about other challenging words in this narrative. If you choose correctly from the menus below, a green border will appear around the word. If you choose incorrectly, a red border will appear.

Now answer these questions about other challenging words in the above narrative.

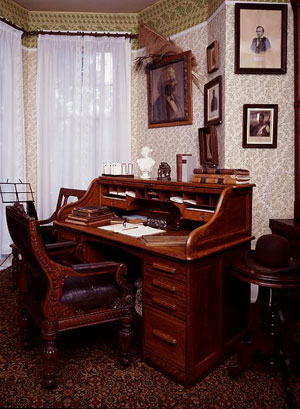

Source: Frederick Douglass den at his home in Washington, D.C., Carol M. Highsmith, Library of Congress

A very impressive man by all accounts, Frederick Douglass was self-taught. He even figured out how to read while performing the unskilled labor of moving a bellows in a foundry. Like Douglass, you can learn many new things on your own, such as the meanings of words. Just remember to apply word-learning strategies as you read. With that advice, thither you go. The word strategies you have learned will help increase your vocabulary, whether you’re reading archaic words like “thither” or words that have yet to be created.