Summarizing Source Material

Source: Dead Girl, Bliznetsov,

istockphotos

The ultra-summarized version of

The Collected Work of Stephen King

It was a nice day............................AND THEN EVIL CAME!

THE END

from rinkworks.com/bookaminute

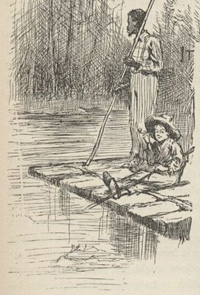

Source: Huckleberry Finn, Project

Gutenberg

The ultra-summarized version of

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Huckleberry Finn

(Goes rafting. Goes home.)

THE END

Source: “Tractored Out,” Dorothea Lange,

Wikimedia Commons

The ultra-summarized version of

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Tom Joad

Our farm has been taken away. Let’s go to California.

(They do. On the way, there are calamities, and people DIE,

because this is the Great Depression when times were HARD,

and it was a struggle just to hold on to one’s DIGNITY.)

THE END

Why summarize?

The purpose of summarizing is to give a brief, objective account of what a lengthy passage says without going into specific details or examples. Summaries are similar to paraphrases in that they are indirect quotations in your own words; unlike paraphrases, however, summaries greatly condense information by capturing just main ideas. They might, for example, reduce a whole page to one sentence, trim an entire chapter or long article to a paragraph, or shrink an even longer source to a few paragraphs. Remember to document and cite summaries because the ideas are not your own.

When?

- Summarize when you want to use a source’s general idea but don’t need to include details or supporting evidence.

- Use a summary to introduce, support, or refute information from another source.

How?

- As with paraphrasing, read the source as many times as necessary to fully understand the material, and then cover the text and write just the main ideas in your own words and own style. Next, check your summary against the original to be sure that you haven’t changed the meaning of the original text or used the same words or phrasing. Remember that simply rearranging words or substituting a synonym here and there is considered plagiarism.

- Be certain that your summary reflects the source’s meaning and intent.

- Name the author (or source if there is no author given) in the summary.

- If you think it’s necessary to keep some of the author’s key terms in your summary, quote them to show that they are not your own. In that case, you will be embedding brief quotes within your summary.

- After you finish summarizing the source, comment and give your own ideas that show the significance of the summary. Including your own ideas or commentary in the body of the summary might confuse your reader. Use signal phrases to make clear what which ideas are yours and which are the source’s.

Now read the following passages. When you’re finished, read the two summaries. Select the one that is accurate and complete.

Source: Writer Zora Neale Hurston, Library of

Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Black male critics were much harsher [than white critics] in their assessments of [Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God]. From the beginning of her career, Hurston was severely criticized for not writing fiction in the protest tradition. Sterling Brown said in 1936 of her earlier book Mules and Men that it was not bitter enough, that it did not depict the harsher side of black life in the South, that Hurston made black southern life appear easygoing and carefree. Alain Locke, dean of black scholars and critics during the Harlem Renaissance, wrote in his yearly review of the literature for Opportunity magazine that Hurston’s Their Eyes was simply out of step with the more serious trends of the times. . . . The most damaging critique of all came from the most well-known and influential black writer of the day, Richard Wright. Writing for the leftist magazine New Masses, Wright excoriated Their Eyes as a novel that did for literature what minstrel shows did for theater, that is, make white folks laugh.

From pages vii-viii of Mary Helen Washington’s foreword to the 1998 reissue of Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston (New York: HarperPerennial, print).

Many of the [New York City] schools with the most devastating academic records are also physically offensive places. At Morris High School, where less than 70 of the 1,700 children in the building qualified for graduation in the spring of 1993, barrels were filling up with rain in several rooms the last time I was there. Green fungus molds were growing in the corners of the room in which the guidance counselor met kids who were depressed. Many of these schools quite literally stink. Girls tell me they won’t use the toilets. They rush home the minute school is over. If they need to use the bathroom sooner, they leave sooner.

From pages 151–152 of the 1995 book Amazing Grace: The Lives of Children and the Conscience of a Nation by Jonathan Kozol (New York: HarperPerennial, print).

For additional examples, refer to the lesson “Summarizing Texts of Varying Lengths.”