Writing Your First Draft

Now that we’ve talked about writing to your purpose and audience, let’s talk about writing your draft. You might be feeling a little overwhelmed thinking about all of the work ahead of you: introduction, body paragraphs, integrating all of the evidence you’ve researched, and writing a conclusion. It is lots of work but it doesn’t have to be overwhelming. Let’s talk about a few strategies for writing a first draft.

Writing the introduction

An introduction is undoubtedly one of the hardest parts of writing a paper. The process of research and writing your thesis usually gives you some idea of what you will say in the body paragraphs of your paper. Your body paragraphs, however, can’t stand alone; your audience has to have some idea of what you are talking about before they get into the body of your paper.

There are three reasons that introductions are important:

- First impressions are crucial. Your introduction not only introduces your topic to your reader, but it also creates a first impression of your writing style and the overall quality of your paper. If your introduction is boring or doesn’t make sense, your reader is going to begin reading your paper with a negative first impression.

- Your reader learns what your paper is about. Your introduction contains your thesis, which is the central argument on which you’ve based your paper.

- Your introduction captures the reader’s attention. A good introduction makes the reader want to continue reading. A great introduction can even make your reader be a little forgiving of minor flaws in the rest of your paper.

Now let’s look at three introductions that demonstrate the reasons given above. Read each introduction, and then answer the questions that follow. Use your notes to write your responses. When you are finished, check your understanding to see possible responses.

- Not all happy animals are alike. A Doberman going over a hurdle after a small wooden dumbbell is sleek, all arcs of harmonious power. A basset hound cheerfully performing the same exercise exhibits harmonies of a more lugubrious nature. There are chimpanzees who love precision the way musicians or fanatical housekeepers or accomplished hypochondriacs do, others for whom happiness is a matter of invention and variation—chimp vaudevillians. There is a rhinoceros whose happiness, as near as I can make out, is in needing to be trained every morning, all over again, or else he “forgets” his circus routine, and in this you find a clue to the slow, deep, quiet chuckle of his happiness and to the glory of the beast.

—“What’s Wrong with Animal Rights?” 50 Essays: A Portable Anthology

- In the first introduction, what does the writer do to make the introduction more interesting?

- What does the first introduction tell you the essay is most likely going to be about?

Sample Responses:

- The writer lists several different kinds of animals and contrasts them. She uses lots of adjectives to give human characteristics to the animals.

- How animals are different even if we describe them as happy

- A few years ago, an article in a supermarket tabloid informed readers of a way to identify aliens who live and work among us. Look for telltale signs, such as fingernails painted with Whiteout instead of nail polish, the article said, and you will be able to identify those visitors from other planets. The thinking behind this intentionally silly article was that aliens are generally acquainted with life on Earth, enough to know that some humans paint their nails. But they haven’t spent time here observing us and so miss the finer points such as exactly what it is that gets painted on fingernails. And it is these finer points that give them away.

Writing for college is, at first, a little like being an alien trying to pass as an earthling. As a college student, you are in a new place, trying to figure out how things work, and you may be unsure of the finer points of composing an essay. Your writing, therefore, may be like the alien with Whiteout on its fingernails: not quite right. You will do things that will give you away as a new college writer. The solution to this problem is to learn to read actively, marking up what you read, taking notes, and reading with a critical eye. This in turn will make you become a better writer.

—“Introduction for Students: Active Reading and The Writing Process,” 50 Essays: A Portable Anthology

- What’s humorous about the second introduction?

- What is the second essay about?

Sample Responses:

- The fact that he compares college students to space creatures

- Learning to write a college essay

- “The nature of watermelon is generally rather chilling and contains a great deal of moisture, yet they possess a certain purgative quality, which means that they are also diuretic and pass down through the bowels more easily than large gourds and melons. Their cleansing action you can discover for yourself; just rub them on dirty skin. Watermelons will remove the following: freckles, facial moles or epidemic leprosy, if anyone should have these conditions.”

—Galen, quoted in the introduction to Choice Cuts: A Savory Selection of Food

Writing from Around the World and Throughout History.

- What captures your attention in the third introduction?

Sample Responses:

- The fact that watermelons go down more easily than gourds, and that watermelons cure skin issues

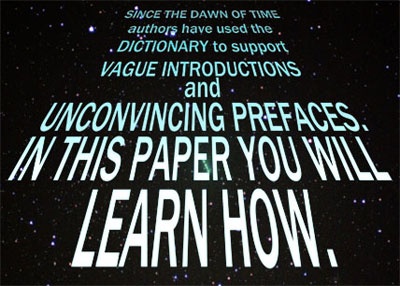

Now let’s turn things upside down and learn about introductions to avoid. While there are certain approaches to your introduction that you might want to consider, there are most certainly a few approaches you want to avoid.

Source: "Since the Dawn of Time…," IPSI

Avoiding introduction pitfalls

- Explicit expressions of your writing goal: “This paper shows that polluting the environment has a negative effect on. . . .” As mentioned above, you put your best foot forward in your introduction. This example sentence and others like it will forecast a dull paper and will be unnecessary in a well-composed piece of writing.

- Definitions from a dictionary: Beginning your paper by quoting the dictionary is a worn out trick. Do not use a version of this statement to introduce your topic: “According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘carbon dioxide’ means. . . .” Introductions of this kind are cliché.

- Grand statements about the past: Although referring to history can play an important role in preparing your reader for your topic and argument, don’t make claims that cover too many years. For example, avoid opening with a statement like “For eons people have been polluting the environment with waste products.” Has your research actually shown this to be true? If not, your paper will be weaker for it. Further, unless your topic happens to span the eons, this kind of opening statement would not be relevant to your thesis. It is likely that you chose a thesis that relates to a narrower span of time.

Here’s one last thought about introductions: If you’re still having difficulty, don’t begin with your introduction. Odd, isn’t it? You might think that you have to start with your introduction, but you don’t. A great deal of weight is placed on the importance of the introduction, and this can sometimes make it more difficult for people to get started. If you don’t know what approach you are going to take to the introduction, you can write it after you’ve written a few body paragraphs, or you can even write it last.

Using an outline

If you’re tempted to skip outlining your research paper, don’t! Many students don’t like outlining because it seems like an unnecessary chore, or they think it takes the spontaneity out of their writing. Research papers shouldn’t be spontaneous; they should be carefully planned. If you need tips on writing an outline, see the Research strand and the lesson “Organizing Major Points and Supporting Information in an Outline.” Your outline is the backbone of your paper, the skeleton that you will use to begin your writing. Using an outline allows you to break up your work into smaller segments. You can use the outline to help you budget your time, as well. For example, you may want to work on your paper today, but you only have an hour between last bell and soccer practice. Your outline can help you determine which of your paragraphs can be written in the time you have to spare. It’s better for you to write in small chunks that you can complete rather than starting and having to stop mid-paragraph.

Similarly, you don’t need to write paragraphs in the order they will appear in the paper. If you use an outline, the content of each paragraph will be planned so you can work on the paragraphs independently. That’s also one of the benefits of using a word-processing program. You can compose your paragraphs in any order and cut-and-paste them into the desired order later on, adding transitions when you revise, making your paper coherent and easy to read.

Source: "Perfection," ChicagoSage, Flickr

Revising the draft

A first draft is referred to as such because it is the first of at least two drafts of your paper. As the saying goes, “All writing is rewriting.” In your first draft, you are going to get your paragraphs down on paper, making sure you have included proper evidence and attributions. After you finish this draft, you’ll revise for tone, transitions, and logic. Finally, you’ll proofread to make sure you have your grammar and mechanics correct.

Writing paragraphs

The paragraphs in your paper should have some common characteristics. As you write paragraphs, you should

- relate each one to your thesis statement by including a topic sentence,

- arrange them in a logical order (there’s that outline again!), and

- develop each paragraph fully by using evidence and details that support the paragraph’s controlling idea.

Creating a strong paragraph using an outline

This plan for writing paragraphs may be familiar to you from your experience writing other types of papers. You can use it to write a longer paper as well, though.

Determine the controlling idea and write a topic sentence. If you’ve done your outline, the controlling idea for your paragraph or set of paragraphs is the element that is in the highest order (usually denoted by a Roman numeral) in your outline. A topic sentence is a mini-thesis statement that tells the central idea of your paragraph.

Let’s use this example thesis for an informative paper about the dangers of suburban deer:

The explosion of new home building in what was once deer territory harms residents, the environment, and the deer themselves.

Let’s also use this of an outline.

I. Urban deer dangerous to people

A. Cause car accidents

1. 1.5 million accidents per year

2. Many deaths attributed to deer/car accidents

B. Cause health problems

1. Carry Lyme disease

a.

Next, let’s use this topic sentence. It corresponds to my outline and relates directly to my thesis statement. I will use this as the first sentence of my paragraph. All of the information in this paragraph will relate to this topic sentence.

Roaming deer on suburban streets have become increasingly dangerous; however, some residents still enjoy watching the deer in their neighborhoods.

- Explain your controlling idea.

They are beautiful and seem harmless, but the deer you see wandering down your street are an accident waiting to happen, particularly during the months of October through December. During these months, deer are mating, and bucks chase does relentlessly without regard to whether this takes them into the path of an oncoming car.

- Provide evidence to support your explanation. This is where you will use quotations and paraphrases of your research.

State Farm, a major insurer of automobiles, estimates that 1.5 million accidents were caused by collisions with deer in 2006. Hundreds of people were killed and thousands injured (CNN). In 2002, in the state of Wisconsin, 16% of all auto crash injuries were caused by collisions with deer (Center For Disease Control). State Farm also estimates that deer vs. car collisions increased 21% nationwide over a five-month period, indicating that the problem is growing exponentially (Eckholm).

- Now, let’s put all of that together.

Roaming deer on suburban streets have become increasingly dangerous; however, some residents still enjoy watching the deer in their neighborhoods. The animals are beautiful and seem harmless, but the deer you see wandering down your street are an accident waiting to happen, particularly during the months of October through December. During these months, deer are mating, and bucks chase does relentlessly without regard to whether this takes them into the path of an oncoming car. State Farm, a major insurer of automobiles, estimates that 1.5 million accidents were caused by collisions with deer in 2006. Hundreds of people were killed and thousands injured (CNN). In 2002, in the state of Wisconsin, 16% of all auto crash injuries were caused by collisions with deer (Center For Disease Control). State Farm also estimates that deer vs. car collisions increased 21% nationwide over a five-month period, indicating that the problem is growing exponentially (Eckholm).

Let’s look back at the outline. The next point states that deer cause health problems. The next paragraph should focus on how "carry Lyme disease" supports the controlling idea that suburban deer are dangerous to people. If you were to continue writing this paper, you would write your draft, going paragraph-by-paragraph through your outline, and you would make sure that each controlling idea is explained and supported by evidence.

Source: Deer storyboard, R8R, Flickr

Wrapping it up

Much emphasis is placed on writing a good introduction, but the conclusion is no less important than the introduction and just as challenging to write. Your conclusion needs to tie your paper together and give your readers a sense that reading your paper was worth their time.

Avoiding conclusion traps

- Don’t restate your thesis. By now, your reader knows what your thesis is. You wrote it in your introduction and spent the entire paper providing evidence to support it.

- Don’t summarize your paper. Don’t do this for the same reason that you shouldn’t restate your thesis. A summary is unnecessary because your readers just read the paper.

- Don’t introduce new ideas. Sometimes, writers are tempted to throw information into the conclusion that they couldn’t find a way to integrate into their body paragraphs. Resist this temptation; it confuses the reader and disrupts the logical flow of your paper.

Writing an effective conclusion

- Choose a side. If your paper covered two sides of an issue—for example, pros and cons of gay marriage—write your conclusion about the side you think has more merit.

- Issue a call to action. In other words, ask your readers to do something with the information you have given them. For example, the section above contains a paragraph from a paper discussing the dangers of the exploding suburban deer population. An appropriate conclusion might be to suggest that communities with this problem work together to find a way to reduce the deer population.

- Write about broader implications. For example, the conclusion of a paper that discusses political satire in popular culture could discuss how many students report getting the majority of their news from The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report rather than from a traditional news source, such as the newspaper.