Source: Camping sign, Ludwig van standard lamp, Flickr

Let’s imagine that you go camping with friends one summer weekend. After setting up camp and having some dinner, you settle back to relax. You can see the sun setting over the valley. There are no sounds of the city or highway, no wind, and not even the sounds of birds. Everything seems perfect.

Suppose that one of your friends is into poetry and hands you a book of sonnets by Wordsworth. Maybe you aren’t excited about this, but you open it up and read the first four lines of “Sonnet 19.” From reading poetry at school, you know to read the sonnet as three sentences, rather than four lines. The sentences it contains are going to mean something different to you in this situation however, than if you read them in a class.

It is a beauteous Evening, calm and free;

The holy time is quiet as a Nun

Breathless with adoration; the broad sun

Is sinking down in its tranquility;

Source: Watercolors Over Desert, Zach Dischner, Flickr

We read in relation to our experience. When we connect our reading strongly with our experience, we read with more interest. When we read with interest, a conversation goes on between what we are reading and our experiences. By the same token, a conversation goes on between what we are reading now and what we have read at an earlier time. How reading one text relates to reading another text is called intertextuality.

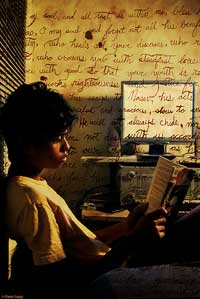

Source: Reading, Dt Fazly, Flickr

Although you read intertextually all the time (whether you choose to or not), the richness that such reading brings is greatly increased when you are aware of how your reading connects to other texts. Imagine the power you can add to your reading by looking at how texts are similar and how they are different. Doing this involves consciously allowing a conversation to occur between what you are reading now and what you have read before that connects to the present text.

In this lesson, you will read and annotate a pair of texts to make inferences, draw conclusions, and synthesize ideas and details using textual evidence. Prepare to get involved in a conversation between you and the two texts you will be reading.