Sentences can be very long or very short or somewhere in between. The lengths of a sentences can lend meaning to writing as well. Let’s look back at the sentences from Sarah Vowell’s “Shooting Dad.”

Source: Sarah Vowell, spoglia, Flickr

Our house was partitioned off into territories. While the kitchen and the living room were well within the DMZ, the respective work spaces governed by my father and me were jealously guarded totalitarian states in which each of us declared ourselves dictator.

The first sentence is succinct and carries the main idea of the paragraph: Sarah and her dad were not getting along. The second sentence is much longer, five times longer, in fact. This sentence builds on the main idea and describes the conflict in terms of war. The author’s sentences are much more interesting to read than this:

Dad and I didn’t get along, so we each had our own work space separate from the other.

Yawn. Boring!

Sentence structures

Let’s review the common types of sentence structures. Sentences are made up of two types of clauses: independent (meaning they can be understood by themselves) and dependent (they need to be attached to an independent clause to be understood). In the examples below, the independent clauses are blue and the dependent clauses are pink.

- A simple sentence is composed of a subject +verb + object, with no dependent clauses.

Example: Susan likes school. - A compound sentence is composed of two independent clauses joined by a coordinating conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so).

Example: Susan went to school, but I didn’t. - A complex sentence has one independent clause and at least one dependent clause. Example: Even though she was sick, Susan went to school.

- A compound-complex sentence is composed of a compound sentence with at least one dependent clause.

Example: Even though she was sick, Susan went to school, but I stayed home.

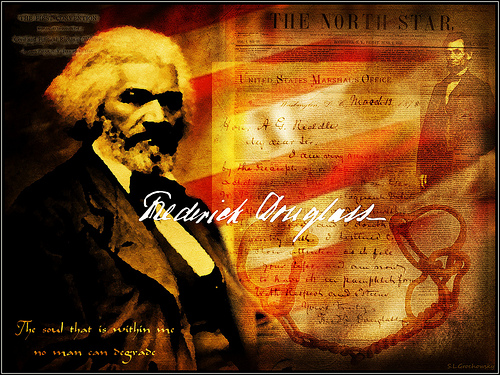

Source: “Frederick Douglass: Man of Truth”, outragousart2008, Flickr

Each of the sentences below comes from Frederick Douglass’s speech “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro,” some of which you read in the previous section. Match each structure to a sentence by dragging each label onto the sentence it matches.

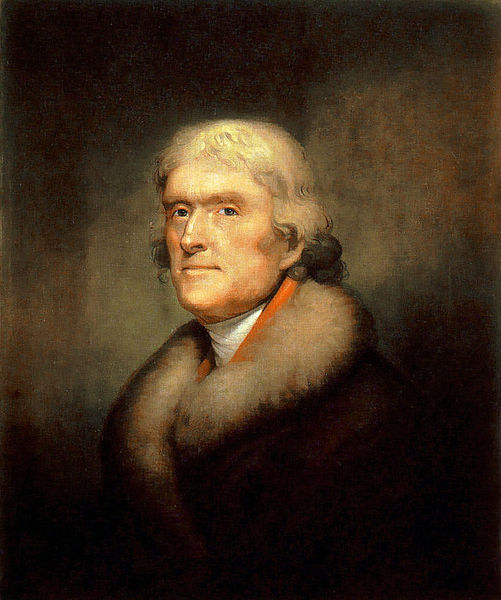

Source: Reproduction-of-the-1805-Rembrandt-Peale-painting-of-Thomas-Jefferson-New-York-Historical-Society 1, Rembrandt Peale.

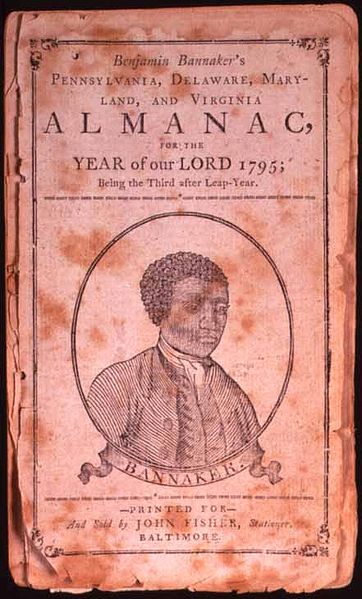

Let’s talk some more about how sentence length lends meaning to writing. Read the excerpt below from Benjamin Banneker’s letter to Thomas Jefferson. Banneker was a former slave with little formal education. He was completely self-taught. He worked with a group that surveyed the original borders of Washington D.C., and corresponded with Thomas Jefferson about the abolition of slavery.

Source: Benjamin Banneker, Wikimedia

SIR,

I AM fully sensible of the greatness of that freedom, which I take with you on the present occasion; a liberty which seemed to me scarcely allowable, when I reflected on that distinguished and dignified station in which you stand, and the almost general prejudice and prepossession, which is so prevalent in the world against those of my complexion.

I suppose it is a truth too well attested to you, to need a proof here, that we are a race of beings, who have long labored under the abuse and censure of the world; that we have long been looked upon with an eye of contempt; and that we have long been considered rather as brutish than human, and scarcely capable of mental endowments.

These are some long sentences! Some of the syntax is related to the time in which it was written, but even so, the sentence length has impact. Banneker wrote to Jefferson to try to convince him that slavery was unjust and to ask him to compare slavery of the Africans to the oppression Jefferson felt under the rule of King George. Banneker needed to show Jefferson that the slaves and former slaves were humans capable of making great contributions to American society, not brutes who could not learn.

Take a look at the first sentence. What can we infer about Banneker’s intention from this sentence? He is acknowledging Jefferson’s position of respect so that he can assure that Jefferson will continue to read. The second sentence directly tackles the world’s opinion of people of color—that they are “brutish” and “not capable of mental endowments.” We can infer that by writing complex sentences with elevated diction, Banneker wants Thomas Jefferson to know that the world’s assumption about his intellect is wrong and that he will make a compelling argument against slavery. Instead of telling Jefferson, “Hey, I am just as smart and thoughtful as anyone else,” Banneker proves it with his writing style.

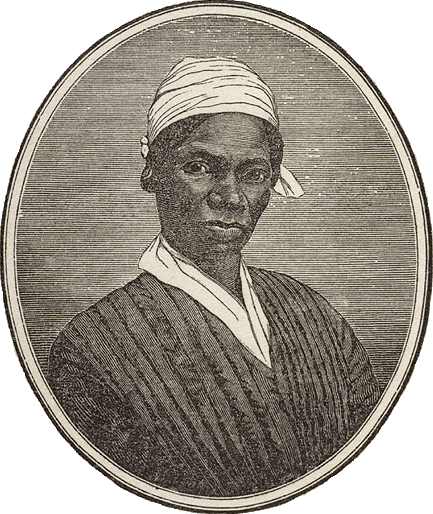

Now, let’s take a look at a speech about equality from one of Frederick Douglass’s contemporaries, Sojourner Truth. She delivered her speech ”Ain’t I a Woman?” in 1851, a year before Douglass’s speech.

Source: SojournerTruth 1850 OliveGilbert, Wikimedia

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?

The diction here is much simpler than either Douglass’s or Banneker’s, and the sentences are much simpler. In fact, there are several simple sentences in this speech.

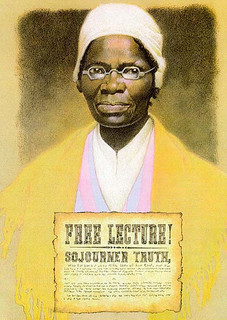

Source: sojourner_truth_lecture_poster[1],

Pamela Y. Cook, Flickr

Use your notes to answer these questions: To whom is Sojourner Truth comparing herself? Why does she ask, “Ain’t I a woman”? What effect does the diction and syntax have on the reader (or listener)? When you are finished, check your understanding to see possible responses.

Sample Responses

- Truth is comparing herself to the white women who men say should be put on pedestals; Sojourner Truth says that while she is a woman just as they are, she is strong, very strong, and just as capable as a man.

- She asks, “Ain’t I a woman?” because she wants the audience to acknowledge that while she is a woman, she is capable of doing many of the things generally assumed to be done by men.

- Truth does not attempt to elevate her diction or to be complex, but her repetition of “Ain’t I a woman?” makes the speech memorable. Though her sentences are short and the diction simple, her speech is memorable because of her counterarguments and experiences that have made her strong.