Source: Planet Energy, Claudio one, Wikimedia

So how do you know whether you’re reading a summary or a critique? The easiest way to tell is to read carefully and decide whether or not the author has an opinion about what is being said. Remember, if you’re reading a summary, the writer should not give you an opinion, only a report of the most significant information.

A critique, however, analyzes, evaluates, and offers an opinion about a text. Think back to the introduction of this lesson and the story of the student who wanted to know about the book. You responded to the student by critiquing, analyzing, evaluating, and finally offering an opinion about the merits of the book. Why is it important to know the difference between a summary and a critique? If you’re reading a critique, you as the reader must make judgments about the quality of the critique.

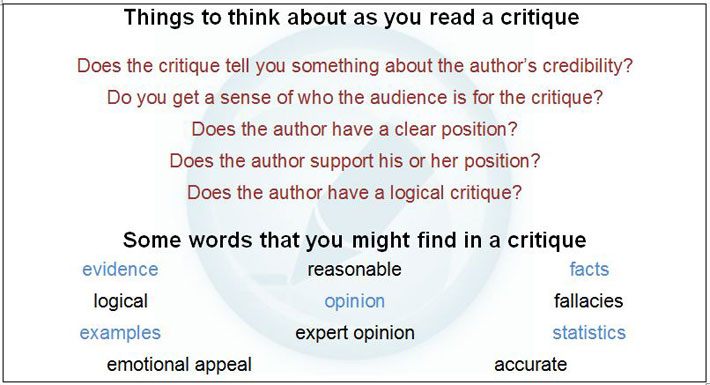

As you think about the difference between a summary and a critique, read the chart below. It contains five questions and some words to help you decide if what you are reading is pure summary or not.

Now, you’re ready to look at a critique of the essay about students and caffeine. If you need to read the article once more, click on the link below.

Teenagers Prefer Drinks with Caffeine

Source: “The End of ‘Energy Drinks’?”, JoeInSouthernCA, flickr

A Critique of “Teenagers Prefer Drinks with Caffeine”

The article “Teenagers Prefer Drinks with Caffeine” by Tara Parker-Pope, health writer for New York Times, is an overview of a research study that looked at whether or not adding caffeine to a drink makes it more appealing. The study was conducted by Dr. Jennifer Temple, author of the study and assistant professor in the department of exercise and nutrition science at the University of Buffalo. She did the study in preparation for a meeting of the Society for Study of Ingestive Behavior in Clearwater, Fla.

The study was conducted with 100 teenagers who sampled flavors of caffeinated beverages and ranked them according to their preference. They were then given their fourth ranked drink; some teens were given caffeine in it, and some were given a placebo. It seemed that the group with caffeine began to rank their drink higher than the group with the placebo, suggesting that caffeine had an effect on flavor selection. However, in the conclusion of the study, students still ranked the drink as fourth whether they had the placebo or not.

While the article described how the study was conducted and who participated in the study, it failed to take into account the underlying problem: is any marketing of caffeinated drinks to teens a good idea? The evidence showed that teenagers were influenced by flavor, but once they made their choices, those choices were reinforced by the caffeine.

In my opinion, the study leaves the door open to producers of these products to increase their efforts to go after the teenage market. It goes without saying that as soon as these markets begin to see a profit, their potentially addictive products will begin to be purchased by younger and younger consumers seeking to emulate the habits and styles of older students.

It may be good that the study indicates teens prefer caffeinated drinks, but I would argue that such a study will lead to the overaggressive marketing of potentially harmful products to teen consumers who are already bombarded by a host of other companies hawking unhealthy products like tobacco and junk food. In other words, the study not only answered a relevant question that many parents might be asking, but it also answered a question for producers of caffeinated products marketed to teenagers.

Using your notes answer these five questions about the critique (The questions appeared in the chart earlier in this section). When you’re finished, check your understanding to see possible responses.

Using your notes answer these five questions about the critique (The questions appeared in the chart earlier in this section). When you’re finished, check your understanding to see possible responses.

Source: Red Bull Long Exposure Experiment, giginger, Flickr

- Does the critique tell you something about the author’s credibility?

- Do you get a sense of who the audience is for the critique?

- Does the author have a clear position?

- Does the author show support for his or her position?

- Does the author have a logical critique?

Sample Response:

- The critique’s author says that the original article was written by Tara Parker-Pope, a health writer for the New York Times. This lends the article credibility since Parker-Pope is qualified to write about a health issues.

- The critique is aimed at the same people who might be interested in the original article—parents of teens and perhaps manufacturers of caffeinated beverages.

- Yes, the author of the critique takes the position that the study should be addressing whether any marketing of caffeinated beverages to teens should even occur.

- Yes, the author of the critique asks a logical question about the study: instead of a study showing if caffeine-laden drinks influence flavor selection, should there be any marketing of caffeinated beverages to teens?

- Yes, the writer notes that the study seems to open the door for more marketing from beverage manufacturers—a logical idea given the information provided in the original article.

Before you try your hand at writing a summary and a critique, let’s pretend that a representative from a manufacturer that makes caffeinated beverages has written a critique of the same article. Remember, critiques contain opinions, so it might look very different from the one you just read.

Can you imagine growing up in this country without caffeinated beverages? Imagine if you will no corner soda shop, no carhops, and none of the iconic advertisements that are so very American. It’s reasonable to suggest that teenagers and caffeine are just as American as mom and apple pie.

The article “Teenagers Prefer Drinks with Caffeine” by Tara Parker-Pope, health writer for New York Times, is an overview of a research study that looked at whether or not adding caffeine to a drink makes it more appealing. The study was conducted by Dr. Jennifer Temple, assistant professor in the department of exercise and nutrition science at the University of Buffalo. She wrote and conducted the study in preparation for a meeting of the Society for Study of Ingestive Behavior.

The study was conducted with 100 teenagers who sampled different flavors of caffeinated beverages and ranked them according to their preference. They were then given their fourth ranked drink; some teens were given a caffeinated drink, and some were given a placebo. The group given caffeinated drinks began to rank their fourth drink higher than the group with the placebo, suggesting that caffeine had an effect on flavor selection. However, in the conclusion of the study, students still ranked the drink as fourth, whether or not they had been given the placebo.

Clearly, the study shows that it is flavor that attracts teenagers to caffeinated drinks. While the early study seemed to suggest that caffeine might influence a teen’s choice, the results clearly demonstrate that the flavors were ranked the same with or without caffeine. The facts show that there is no connection between drinking caffeinated beverages and preference for a particular flavor.

This study is simply one more effort to regulate an industry that has been a mainstay of American manufacturing and culture for well over a hundred years. In my opinion, the results of the study logically prove what we have known all along: manufacturers rely on taste and marketing to capture the teenager market. As producers of quality drinks, we will do what we have always done—provide refreshments as iconic as their advertising.

Do you see the difference in opinions? Both writers read the same article but came to very different conclusions. As you can see, it’s up to you to make up your own mind when you read a critique. If you are a knowledgeable reader, you will be able to tell where the summary and facts leave off and where the opinions begin.