Source: Hon. Hiram R. Revels of Miss., Library of Congress

Many people associate the civil rights movement with the 1960s, but the roots of this movement started well before the turbulent decade of the '60s. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 granted African-American men citizenship and the same rights as white men. In 1870, the 15th Amendment was ratified, giving African-American men the right to vote. During the Reconstruction era, hundreds of African Americans were elected to national and state offices.

Source: Hon. Hiram R. Revels of Miss., Library of Congress

With such diversity in state and federal governments, African-American legislators, like Hiram Revels, passed civil rights legislation. An additional civil rights act was passed during Reconstruction. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 said that all Americans, regardless of race, should have full and equal access to public accommodations such as restaurants, theaters, and public transportation.

Congress made both of these acts law, extending equal rights to more Americans. Actually, the opposite occurred. Neither of these acts was enforced, and the U.S. Supreme Court declared the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional in 1883.

In 1896, the Supreme Court established the doctrine of “separate but equal” with the court case of Plessy v. Ferguson. The court decision affirmed that separating whites and blacks was constitutional if the facilities were equal. The decision was a major setback in the ongoing struggle for equality and civil rights for African Americans.

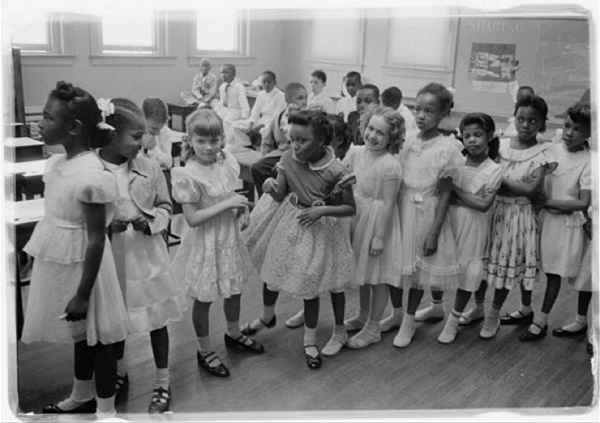

One of the most decisive moments in the fight for civil rights occurred in 1954 with the Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education, which declared that the racial segregation of children in public schools denied equal access to education and was therefore unconstitutional.

Source: ppmsca03119, Library of Congress

Although Brown v. Board of Education did not address voting rights, it did set the tone for legislation to address voting and other civil rights for all Americans. Read the excerpt from President Dwight Eisenhower's address at the Hollywood Bowl in 1956.

We have erased segregation in those areas of national life to which Federal authority clearly extends. So doing in this, my friends, we have neither sought nor claimed partisan credit, and all such actions are nothing more—nothing less than the rendering of justice. And we have always been aware of this great truth: the final battle against intolerance is to be fought—not in the chambers of any legislature—but in the hearts of men.

Address at the Hollywood Bowl, Beverly Hills, California, 10/19/56

Based on this quotation, what was Eisenhower's position on civil rights? Considering the changes in the country during this time period, do you think President Eisenhower addressed civil rights during his term?

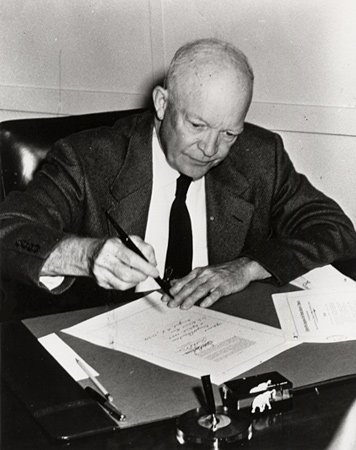

Source: Civil Rights Civil rights Act, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum

In 1957, President Eisenhower proposed new civil rights legislation. He was successful as the Civil Rights Act of 1957 was passed. This act provided federal enforcement against interference with the right to vote. The act also established the Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department. The Civil Rights Act of 1957 also established a federal Civil Rights Commission, which could investigate instances of discrimination and recommend solutions. On September 9, 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

![]() Click on the document below to read a summary of the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Click on the document below to read a summary of the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Read the following excerpt from the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and answer the questions that follow in your notes:

"No person, whether acting under color of law or otherwise, shall intimidate, threaten, coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten or coerce any other person for the purpose of interfering with the right of such other person to vote or to vote as he may choose."

Interactive popup. Assistance may be required.

No person, even if he or she is in law enforcement, may interfere with another person’s right to vote.

Interactive popup. Assistance may be required.

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 alone was not enough to protect the voting rights of all Americans. More laws and amendments had to be passed after 1957 to protect voting rights for Americans.

![]() Click on the pamphlet below.

Click on the pamphlet below.

Continue answering the following questions in your notes.

Interactive popup. Assistance may be required.

The Commission reported its findings of interference with voting rights to the President and Congress; the Commission made recommendations for government action against the infringement of voting rights.

Interactive popup. Assistance may be required.

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 did promote equality in extending voting rights to all Americans and establishing a government agency to protect those rights.

Source: Strom Thurmond speech, Wikimedia

There was strong opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1957. This is a photo of Senator Strom Thurmond (South Carolina) who supported racial segregation with a 24 hour filibuster (nonstop talking in an effort to stop an action in Congress). His attempt was unsuccessful, but it showed how deep the opposition was, especially in southern states.

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 turned out to be relatively ineffective due to so much opposition. In fact, by 1957, only 20 percent of eligible African-American voters were registered to vote; by 1960, fewer blacks were voting than in 1956.

Strom Thurmond was not the only oppositional force to civil rights. The governors of some of the southern states also strongly opposed civil rights for African Americans during the 1950s and 1960s.

![]() Click on the images below to read more.

Click on the images below to read more.

Sources for images used in this section, as they appear, from top to bottom: