Introduction

from “The the impotence of proofreading” by Taylor Mali

Has this ever happened to you?

You work very horde on a paper for English clash

And then get a very glow raid (like a D or even a D=)

and all because you are the word's liverwurst spoiler.

Proofreading your peppers is a matter of the the utmost impotence.

If you're like most of us, the experience described above has indeed happened to you. It's demoralizing to get back an essay or research paper with a lower grade than you expected and with a note from the teacher that says “Proofread!” However, unless you systematically proofread your writing—instead of never looking back over it or just quickly scanning it thirty seconds before it's due—chances are you will continue to be disappointed with the grades and comments on your papers. Although you probably won't find proofreading listed on The World's 10 Most Exciting and Fun Activities, be assured that checking your writing carefully will pay off in a variety of ways. Time spent proofreading is never wasted.

Many people use the terms proofreading and editing interchangeably, but we are going to differentiate between them. The titles of the first five lessons in Writing, Module 5, begin with the word “editing”; those lessons deal with checking a paper's content, structure, clarity, transitions, style, and troublesome grammar. You edit throughout the writing process to develop, connect, and organize your ideas in the best possible way.

© 2007 by Kittyz202

© 2007 by Kittyz202 The majority of proofreading, on the other hand, happens toward the end of the writing process, usually just before you hand in the final paper. Although you do some proofreading along the way, remember that sentences and paragraphs will change as you edit. The paper simply isn't finished until you've proofread it after the editing process. Yes, content is the most important element of a written piece, but if it is marred by surface errors, the quality of your writing and the coherence of your ideas suffer. In this lesson, we'll tackle proofreading for the three kinds of technical errors that can spoil otherwise good papers: poor spelling, capitalization, and punctuation.

Before we get started, though, let’s be very clear about something: ALL writers, not just high school students, make mistakes. Think of authors whose works you like to read. Regardless of how many names come to mind, rest assured that all of them have had errors in their writing just like you. A major difference between them and you is that they have professional proofreaders and editors go over their work; you, however, don’t have that luxury, so proofreading is your responsibility. You can either (1) not check your writing for surface errors and hope for the best—obviously not a good idea—or (2) improve your proofreading skills and thus improve your papers. Since you're here, we assume you chose the second option.

General Tips for Successful Proofreading

© 2008 by Paul Englefield

© 2008 by Paul Englefield

Although you want to be a better proofreader, you're probably thinking that you don't need to read these tips, aren't you? Well, if you're serious about finding and fixing your errors before your teacher does, you DO need to read them. The suggestions below are about proofreading in general, but in later sections of the lesson, we'll discuss specific proofreading techniques for specific types of errors. Experiment with them to determine which ones work best for you, and then use them to develop your own systematic strategy.

- Know which mistakes you repeat. Why continue, essay after essay, to make the same mistakes when it is within your power to eliminate most of them? Keep a list of your errors so you can target those mistakes you repeat. We’re talking about the errors you make because you really don't know the proper way to spell, capitalize, or punctuate a word or sentence. Armed with that list and a handbook, dictionary, or computer, you can begin to chip away at repeated errors by zeroing in on them and learning how to correct them.

- Wait awhile before proofreading a paper. If you check for errors immediately after you finish a writing assignment, you're likely to be thinking about what you meant to write, not necessarily what you actually did write. You may skip over mistakes unintentionally. Put the essay away, even if for only an hour, and come back to it when you've had time to clear your mind. You'll probably be able to spot errors more easily after you and your paper have had a vacation from each other.

- Allow yourself plenty of time. Proofreading is the final step of the writing process. Carefully check for errors and correct them without rushing.

- Use a hard copy. If you write your paper on a computer, print a copy to proofread instead of trying to check it while looking at the screen. You'll be amazed at how many more errors you'll catch that way.

- Change the format. An unfamiliar piece of writing is easier to proofread than the same old essay you've been working on and know by heart, so use the computer to trick your brain into thinking you're checking a different paper. Simply change how your paper looks by altering the kind of font, the size, color, or text spacing before you print a copy to proofread.

- Proofread in a quiet place. Yes, we realize that quiet places and teenagers don't usually go together. However, we also know that a writer needs to focus and concentrate to proofread well. All those things that make noise will wait patiently for you to return.

- Focus on one kind of error at a time. As you'll find out in the following sections, there are some proofreading techniques that work well for specific kinds of errors but don't work as well for others. Don't try to find and fix all of them at once.

Now let's move on to proofreading for particular kinds of errors.

Proofreading for Spelling

In 1988 the University of Wisconsin awarded thousands of diplomas with the glaring spelling error Wisconson on every one of them. Amazingly, six months passed before anyone noticed this blunder. A university official at the time insisted that the diplomas had been proofread, but only to check students' names and degree subjects—not any of the “standard information” like the name of the state.

Ouch! The moral of that story is to proofread everything, because errors can happen anywhere in a written document. People have even misspelled their own names, obviously not because they didn't know the correct spelling, but because it never occurred to them to proofread every word they wrote.

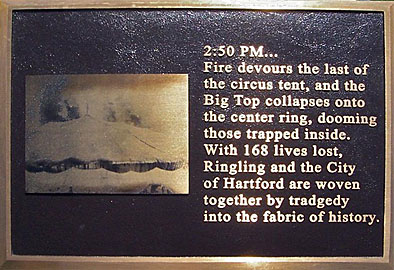

Writing done on a computer or paper can be easily corrected, but that's not the case if the writing is chiseled in stone or cast in metal like the text below, which appears on an established monument. Can you spot the spelling error? When written words are involved, no person or document is safe from mistakes.

Basically, there are two kinds of spelling errors: those that are easy to find and fix, and those that are not so easy.

First, there are misspellings in which words aren't really words at all (teh instead of the, begining instead of beginning). You can usually catch such typos or mistakes, either on your own or with an electronic spell-checker—IF you proofread, have access to a computer, and use the spell-checker.

The second type of error threatens your writing more, though, because the misspelled word actually is a word, just not the right one (witch for which, bore for boar). Many errors of this kind are caused by homophones, which are closely related to homonyms. The bad news is that spell-checkers will miss most word errors of this kind in the text. In other words, the computer misses precisely the errors that people have a hard time finding. So if you depend on your spell-checker to take care of everything, think again. When electronic gadgets can't proofread efficiently, you're going to have to do it yourself. Still not convinced? Read the following stanzas of a poem about this exact topic.

Candidate for a Pullet Surprise

(often called "An Owed to the Spelling Checker")

by Mark Eckman and Jerrold H. Zar

I have a spelling checker.

It came with my PC.

It plane lee marks four my revue

Miss steaks aye can knot sea.

Eye ran this poem threw it,

Your sure reel glad two no.

Its vary polished in it's weigh,

My checker tolled me sew.

A checker is a bless sing,

It freeze yew lodes of thyme.

It helps me right awl stiles two reed,

And aides me when aye rime.

Each frays come posed up on my screen

Eye trussed to bee a joule

The checker poured o'er every word

To cheque sum spelling rule. . . .

Imagine you're left to proofread on your own, without access to a computer or spell-checker. You can only be efficient as a spelling proofreader if you keep in mind some major spelling rules. Notice that with almost all of the following rules, there are multiple exceptions that make you want to tear your hair out. If it makes you feel any better, those exceptions make writers, grammarians, and English teachers everywhere want to tear their hair out, too. Causing additional hair-pulling, British and American spellings of many words differ even though English is the common language. With all those things in mind, let's take a quick look at some of the wild and crazy American English spelling rules you should know in order to be a better proofreader.

- IE/EI:

Use I before E, except after C or the long sound of A, like neighbor and weigh.

i before e believe friend siege chief niece ei after c receive ceiling receipt conceive deceit ei sounds like long a eight vein sleigh freight weight

Some exceptions: either, neither, leisure, weird, seize, seizure, foreign, forfeit, height, protein

- Prefixes:

When adding a prefix, the spelling of the base word remains the same. (Ironically, one of the most misspelled words is misspell. The prefix mis- is simply added to spell, so the word has two s's, not one.)

Some exceptions: This rule doesn't have any exceptions, but a few prefixes can be followed by a hyphen (for example, self-, all-, ex-). - Keeping or dropping a silent “e” at the end of a word:

(1) Drop the final e when adding an ending that begins with a vowel (surprising, guidance).

(2) Keep the silent e when adding an ending that begins with a consonant (careful, accurately).

Some exceptions to (1):

dyeing (so it's not confused with dying); mileage (so it's not mispronounced incorrectly as milage); noticeable, courageous (so the words will retain the soft rather than the hard sound of c or g)

Some exceptions to (2):

words like truly (not truely) and argument (not arguement) in which the silent e is preceded by another vowel - Keeping or dropping a “y” at the end of a word:

(1) With words ending in y preceded by a consonant, change the y to i before any suffix not beginning with i (beauty becomes beautify, worry becomes worried).

(2) Keep the y when it follows a vowel or when the suffix starts with i (pray becomes prayer, study becomes studying). - Plurals:

The regular way to form the plural of a noun is to add s to the singular form (boys, books, chairs).

Some exceptions: leaf, leaves; life, lives; child, children; mouse, mice

—Singular nouns ending in s, sh, ch, or x form the plural by adding es (dresses, bushes, beaches, boxes).

—Nouns ending in o preceded by a vowel usually form the plural by adding s (radios, rodeos).

—Nouns ending in o preceded by a consonant usually form the plural by adding es (heroes, potatoes).

Some exceptions: solo, solos; soprano, sopranos; piano, pianos

- Using the right word:

Yikes! You know there are lots of homophones, and you know that you sometimes use the wrong ones. Since a spell-checker is useless for this problem, you need to recognize and know the meaning of as many homophones as possible. Click here to link to a site that has an alphabetized list of hundreds of homophones. After you click on a letter of the alphabet (scroll to see the list), you can click on any word to find out its meaning.

Strategies to proofread for spelling

© 2008 by 92wardsenatorfe

- Most people misspell the same words over and over, so the most helpful strategy for catching spelling errors is to know your own error pattern—the words that always give you trouble. Keep an alphabetized list of the words that trip you up and use it as a reference for proofreading.

- A suggestion that goes along with the previous one is to turn off the spell-checker and only switch it on after you've finished writing. That will enable you to see which spelling mistakes you repeat in your writing.

- Read your paper out loud. This forces you to read each word individually and increases the odds that you'll find misspellings, especially typos and homophones.

- Read each word individually, from right to left, starting at the end of your paper. Yes, that's going backwards, word by word. Because content, punctuation, and grammar won't make any sense, your focus will be entirely on the spelling of individual words.

- Remember the low-tech, tried-and-true strategy: keep a dictionary handy and use it to confirm any word you're unsure about. A computer dictionary is certainly helpful, but it likely falls short of a good college-edition dictionary in paper or CD form. If your spell-checker suggests a bizarre correction for one of your words, don't automatically accept it; instead, use a dictionary to be sure.

© 2008 by 92wardsenatorfe

© 2008 by 92wardsenatorfe And here’s one last thought about spelling. In the world of texting, blogging, e-mailing, and social networking, spelling shortcuts have become the norm. Although “C U 4 lunch 2moro” might be understandable as a quick electronic message to your friend, those condensed versions of words won't make sense in most other writing situations. Certainly, textese works for casual written exchanges; however, appropriate language is essential for more formal writing such as letters, applications, academic papers, and business correspondence. Consider the subject, occasion, audience, and purpose of what you're writing. When you take all those factors into consideration, it's easy to see that both textese and conventional spelling have their places in modern communication.

To check your general spelling knowledge and to gauge your ability to choose correct homophones and differentiate among commonly confused words, take the interactive quiz here.

Proofreading for Capitalization

You're probably wondering why there's a section about capitalization in a lesson for high school students. After all, you learned all the capitalization rules years ago, right? That may be true, but problems with capitalization keep showing up in high school papers. For you to become an effective proofreader, you need to be sure about capitalization principles that you might not have formally studied in a long time. While we certainly aren't going to discuss every capitalization rule—thank goodness—we are going to review a few that many high school writers either don't remember or don't understand.

- all the important words in a title, including the first and last. Don't capitalize an article, short preposition, or coordinating conjunction unless one of these is the first or last word.

- geographical names that refer to a specific place like the Rocky Mountains. Do not, however, capitalize north, south, east, or west if you're indicating directions; do capitalize them when referring to recognized sections of the country (“Students from the South who go to college in the Northeast have trouble dealing with the bitterly cold weather”).

- the formal name of a specific course, school, or college but not when the name is used as a common noun (“I took Physics I at Wilson High School, but I won't take another physics class at the University of Texas”; “I took a physics course in high school, but I won't take another one in college”).

- the names of relationships only when they form part of a person's name or substitute for a person's name (“I didn't want Aunt Helen to leave, but I hoped my uncle would go”; “I saw my mother at the store, but Dad wasn't there”).

- most titles of persons only when they precede the persons' names (Senator John Smith or John Smith, the senator; Doctor Marie Carter or Marie Carter, a doctor; General Omar Bradley or Omar Bradley, the general; before the club president opened the meeting; four state representatives who attended the conference).

Exception: It is generally acceptable to capitalize the title of a very high-ranking official or person held in esteem even when that title follows a proper name or is used alone (the President of the United States, the Chief Justice). - races, nationalities, and languages (Native American, Caucasian, Germans, Italian).

- the first word of a quotation (“Mary said, ‘She is so thin that she can squeeze through the opening.'”)

- the word Internet.

Strategies to proofread for capitalization

Carefully read your paper one sentence at a time to confirm that you capitalized words you should have and didn't capitalize those you shouldn't have. Ask yourself if you're saying what you mean to say. Is each word the right one, or do you change its meaning by making it uppercase or lowercase? When in doubt, look it up in a dictionary, which will usually tell you if a word has a different meaning when it is capitalized.

NOTE: As mentioned in the spelling section, always consider the subject, occasion, audience, and purpose of what you're writing. You might text “i luv u,” but in other forms of writing, please don't use a lowercase letter for the singular pronoun “I” or start a sentence with a lowercase letter. Those errors break the two most basic capitalization rules.

To check your understanding of how to proofread for capitalization, take the challenging interactive quiz here. After you finish the quiz and get your score, you may want to review capitalization some more. If so, click on the “Capitalization” link on the quiz page.

Proofreading for Punctuation

Punctuation, to most people, is a set of arbitrary and rather silly rules you find in printers' style books and in the back pages of school grammars. Few people realize that it is the most important single device for making things easier to read. —Rudolf Flesch

Now we've come to one of the tougher parts of proofreading: locating and correcting punctuation errors. We'll briefly touch on most kinds of punctuation, but we'll look a little closer at the ones that give students the most trouble. As with spelling and capitalization, we know you've been using these punctuation marks for years; however, to do a good job of proofreading, you need to refresh your memory about functions you might not have studied recently.

| Periods:

|

| Question Marks:

|

| Exclamation points:

|

| Em dashes:

|

|

Parentheses:

|

|

Brackets:

|

|

Hyphens:

|

| Ellipses:

|

|

Colons:

|

| Semicolons:

|

|

Apostrophes:

|

| Quotation marks:

|

| Commas: (There are many more comma rules than the ones below, but these particular rules are broken most often.)

|

Strategies to proofread for punctuation

© 2010 by Mike Cogh

© 2010 by Mike Cogh

- You have been writing essays and other types of papers for years, so you know which punctuation has caused problems for you in the past. Check carefully for the punctuation errors that have kept showing up in your writing.

- Read your work out loud because hearing the words can sometimes give you hints as to where punctuation is needed. The emphasis and length of pauses can serve as hints, too, about which punctuation is appropriate.

- Read your writing silently, one sentence at a time, starting at the end and working your way to the beginning of the paper. It's easier to notice punctuation and some other types of errors when you're not reading the content in proper order.

- If you get stuck on which punctuation to use in a certain situation, don't just guess; instead, take the time to look up the information you need. The time will not be wasted because you can use it as well as add it to your knowledge bank for future papers.

As a culminating activity, see how well you can proofread for all kinds of punctuation by doing two short quizzes.

Click here for the first quizzes and click here for the second. They are different, and each gives you immediate feedback.

Good luck with your proofreading!

Resources

Please note that the resources open in a new window/tab in your browser. To return to this lesson, close the additional resource window/tab.

Resources Used in this Lesson: Bibliography

Aloisi, Al. “A Complete Homophone List.” Homophone.com.

Cagle, Emily. “Embarrassing Errors – The Ten Biggest Proofreading Gaffes.” Ezine Articles: Writing and Speaking. September 4, 2009.

Farrell, Jim. “A Circus Fire Addendum.” iTowns(blog). Hartford Courant. April 16, 2008.

Fowler, H. Ramsey, and Jane E. Aaron. The Little, Brown Handbook. New York: Pearson Education, 2007.

“Interactive Quizzes.” Guide to Grammar and Writing. Capital Community College Foundation.

Mali, Taylor. “The the impotence of proofreading.” Taylormali.com.

Nordquist, Richard. “The Spell Checker Poem, by Mark Eckman and Jerrold H. Zar: The Facts Behind ‘Candidate for a Pullet Surprise.'” About.com Grammar & Composition.

Simmons, Robin L. “Exercises at Grammar Bytes!” Grammar Bytes!. Accessed January 4, 2011.

“SMS Language.” Wikipedia. Last modified January 2, 2011.

Trimble, John R. Writing with style: Conversations on the art of writing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1975.

Warriner, John E., and Francis Griffith. English Grammar and Composition: Complete Course. Dallas: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977.

Writer's Choice: Grammar and Composition, Grade 12. Peoria: Glencoe/McGraw-Hill, 2001.