Introduction to Lesson

Information is everywhere these days, and you don’t have to look too hard to find it: 24-hour news channels, millions of websites, searchable databases, online journal and magazine articles, and of course books (more of them being published on more topics than ever before).

The key to succeeding in this information era is to harness information’s power through effective, thorough research.

What is research?

When you do research, you learn more about a subject by exploring existing knowledge such as books, magazine articles, journal articles, and online databases, which are all examples of secondary sources. You can also create your own primary sources by surveying others, conducting experiments, and conducting interviews.

There are two different types of research: primary research and secondary research.

Most of the research you are going to do is considered secondary research, so let’s begin there.

Secondary research is called secondary because someone other than you has made the observations, done the experiments, conducted the interviews, or conducted the surveys. Secondary research involves reading books, articles, or websites about your topic. Most of the research you will do is considered secondary research.

When you conduct primary research, you gather information about a subject by conducting experiments, surveys, interviews or recording your observations about the world around you. If you’ve taken a science class, you probably did primary research. For example, if you grew crystals in chemistry class, recorded your observations about how they grew (what patterns, how large, how fast), and wrote a lab report about what happened, you conducted primary research.

In this lesson, we’re going to learn how to plan our research, find primary and secondary sources, and use those sources in our research papers.

Making a Research Plan

As we discussed earlier, we live in the “information era.” With sources everywhere, from the library to the Internet, it can be confusing and intimidating to know where to start and what sources to use. We need to create a research plan to help us navigate through the sources available for our topic.

In another lesson, “Generating Ideas and Questions about a Research Topic,” we developed a research question:

“Can grazing cattle be good for the environment and affordable for the consumer?”

Craft a strong research question before planning your research. This will give your research direction and keep you from exploring irrelevant sources. Having a research plan can keep you from feeling frustrated because you can’t find enough information. It will also keep you from feeling overwhelmed by having to wade through too much information before you find sources use can use.

The first thing we need to do when planning our research is figure out what we already know. Then we can see what we still need to learn about our topic. Let’s begin by asking a few questions about our research question. This is similar to the brainstorming we did in the previous lesson. Let’s complete the pre-research questions below.

First, open the Pre-Plan Chart provided as a PDF. You may download and type into the PDF or print it, and write your answers as we step through the pre-planning process.

View the Pre-Plan Chart on ScribdNext, write your research question. Our example is, “Can grazing cattle be good for the environment and affordable for the consumer?” We need to figure out what we already know about the topic. Type anything you can think of about grazing cattle versus feeding them in a lot: Is it better for the environment than feeding cows grain? Is it more or less expensive than feeding them grain? If you worked through the lesson about generating a research question, you might remember the research we did to refine our question. If you didn’t do that lesson, don’t worry; just write downwhatever you can think of about the question.

In the space provided, write at least three questions that you need to explore in order to understand your research question.

Finally, for each question you generate, write the kinds of sources you might use to find the answer to that question. For example, you might need journal articles, newspaper articles, books, websites, or interviews. You do not need to know any specific sources at this time.

When you have completed the chart, check your understanding below to see how I completed the chart.

Research Question: “Can grazing cattle be good for the environment and affordable for the consumer?”

| What do I already know about my research question? | What do I need to learn to better understand my research question? | For each question, provide a type of source that might help you answer the question. |

Cattle raised on feed lots aren’t good for the environment. |

Is grazing cattle better for the environment than keeping cows on feed lots? |

Journal articles, magazine articles, books |

Cattle raised on feed lots are cheaper because more cows can be kept on smaller plots of land. |

Can grass-fed beef be affordable for the consumer? |

Journal articles, magazine articles, books |

Can beef from grazing cattle be made cheap enough for restaurants to use it instead of conventionally-raised beef? |

Interviews with ranchers who graze cattle, magazine articles, newspaper articles |

|

Do any chain restaurants use grass-fed beef? |

Internet search, chain restaurant websites |

|

| Will people eat less beef to protect the environment? | Survey |

Let’s review the chart together. In the first column, I wrote a few things that I learned while I was creating my research question. I included information from doing the brainstorming activities, watching the movie trailer, and reading the newspaper article—things that helped me come up with the question in the first place.

In the middle column I wrote five questions that I still need to explore in order to answer my research question and write a good thesis for my paper.

In the third column, I wrote where I would likely find the answers to these questions. I wrote down mostly secondary sources: articles, books, and websites. But I also thought that I could interview a rancher who grazes cattle to answer the question “Can beef from grazing cattle be made cheap enough for restaurants to use it instead of conventionally-raised beef?” This would be primary research I would conduct. I also thought I might conduct a survey to see whether people would be willing to eat less beef if it’s better for the environment. Not all research projects will require primary research, but primary research can be a way to get information that I might not be able to get otherwise.

What’s next? We need to decide where we are going to look for answers. It’s time to talk about finding specific sources. In the next section, we’ll learn about finding secondary sources.

Which Secondary Sources Are Right for You?

As I mentioned earlier, secondary sources are sources that contain other people’s knowledge about your subject. They have conducted experiments, interviews, or surveys; made observations; and published their results for others to read. Journals, magazines, newspaper articles, books, and websites are all secondary sources. Let’s look at the pros and cons of different kinds of secondary sources.

Traditional Print Sources |

||

|---|---|---|

| Type of Resource | Pros | Cons |

| Books |

|

|

Academic Journals

|

|

|

Trade Journal Articles |

|

|

Popular Magazine Articles |

|

|

Newspaper Articles |

|

|

Finding Print Sources

The best place to find print sources is in the library. Almost all libraries have online catalogs that allow you to search for sources by author, title, subject, or keyword.

Searching for Books

When you get to the library, the easiest book searches are by author or title. Searching by author is exactly as it sounds. If you know a book’s author, you can type the name into the search field, and you will retrieve a list of the books by that author that your library owns or can get for you through interlibrary loan. Some catalog author searches require you to type the last name before the first name, maybe with a comma separating the two. If you are having trouble, ask a librarian for help. When you search by title, you simply type the title into the search field to find out if the library owns the book and where it is kept.

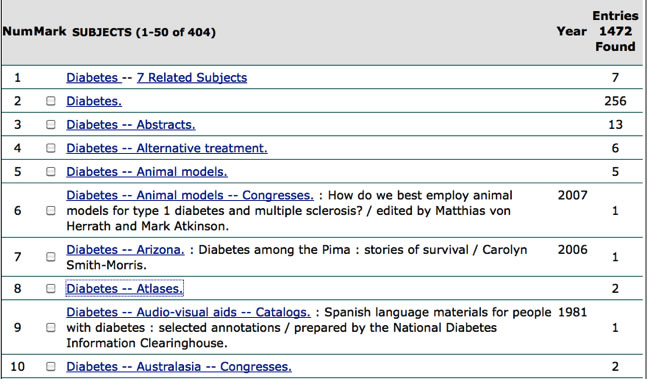

When you first start your research, you probably aren’t going to have an author or a book title to search for. Let’s talk about searching by subject and keywords. If you’re just starting to brainstorm your research topic, you might have a very general subject, for example, diabetes. If you type the word, “diabetes” into the catalog’s subject search field, you will retrieve a page that looks similar to this:

There are 1,472 books with diabetes as part of their subject. Notice that the subject categories get very narrow. For example, entry seven is the subject of diabetes in Arizona. Browsing a subject list can help you to hone in on a specific direction to take your research.

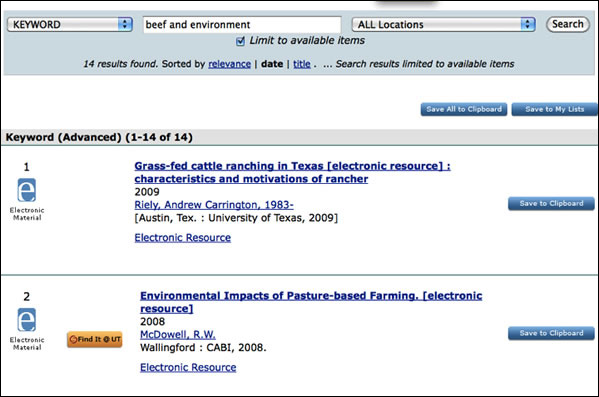

Let’s go back to our research question, “Can grazing cattle be good for the environment and affordable for the consumer?” One of the things we want to learn about is the environmental effect of consuming beef. I can type “beef and environment” into the keyword search field, and retrieve fourteen books that have those keywords. Results for keyword searches appear in order of relevance, meaning that the source that most closely matches the keywords appears first. The source that most loosely matches the keywords appears last.

These first two entries in my results look like excellent sources for my research.

You can use a similar keyword search to look for journal, newspaper, and magazine articles. Libraries now have online databases that house abstracts—or summaries—and full-text articles. We will learn how to use these databases in another lesson titled, “Utilizing Databases, Electronic Sources, and Print Sources.”

Electronic Sources

Often when we refer to electronic sources, we mean the Internet, or the World Wide Web. Sometimes I think the World Wide Web should be renamed the Wild, Wild Web because of its similarities to the Wild, Wild West. Like the US expansion to the West, the web has opened us up to valuable experiences, but it can also be a dangerous place in terms of information. Anyone can put information on the web, so you have to be extremely careful when using web sources in research. We will discuss how to determine whether a source is valid in a lesson called, “Determine the Validity and Reliability of Sources,” but for now let’s talk about the kinds of information you can find on the web and the pros and cons of each.

Electronic Sources |

||

|---|---|---|

| Type of Resource | Pros | Cons |

Websites |

|

|

Blogs

|

|

|

Listservs, Bulletin Boards, and Discussion Groups/Forums |

|

|

Multimedia |

|

|

Now that you understand secondary sources, let’s talk about primary sources and when to use them.

Which Primary Sources Are Right for You?

Primary sources include experiments, surveys, interviews, and observations that you conduct to gather information about your research question. Not all research projects require primary research, but sometimes it might be the only way to get the information that you need.

Let’s go back to the research plan that we made earlier. One of the questions that we need to answer is, “Can beef from grazing cattle be made cheap enough for restaurants to use it instead of conventionally-raised beef?” I thought we might need to interview ranchers who raise grass-fed beef. An interview can help you find out what people most affected by an issue think and feel about it. A rancher would know whether it’s possible to meet the current demand for beef with cattle that are grazed rather than raised on a feed lot. Beginning with interviews, let’s look at the types of primary research you can conduct.

Interviews

When you interview people, you ask them specific questions that will help you to answer your research question. You can do interviews in person, by phone, by e-mail, by instant message (IM), or by chat. In-person or phone interviews are preferable because they allow you to ask follow-up questions, but sometimes they aren’t possible, so e-mail and IM interviews are OK too. Let’s talk about what makes a successful interview, and then we’ll discuss how to create good questions.

How to Choose an Interview Subject

- Choose an expert. Do you want the opinion of an expert on your topic? In our research plan, I suggested that an interview with a rancher who raises grass-fed beef would be a good source for our paper. A local university is a good place to find experts in any field. You can contact the academic department that teaches your subject and ask if there might be a professor willing to be interviewed. Local businesses and professional organizations are also good places to find experts to interview.

- Choose someone experienced with your topic. If you were writing a paper about the dangers of texting while driving, you could interview a person who was involved in a texting-while-driving accident. Finding someone with experience could be as easy as asking your friends and family members whether they know someone you could interview, or you could post an interview request on an online discussion forum that deals with your topic.

Tips for Writing Good Interview Questions

- Avoid bias. Biased questions lead your subject to answer them in a certain way. For example, “Don’t you agree that eating meat is bad for the environment?”

- Ask open-ended questions. Don’t ask questions that encourage one-word answers. Don’t ask, “Did you become a rancher because your father was a rancher?” Ask, “Why did you become a rancher?”

- Don’t make your questions too complicated. Ask concise, specific questions.

Let’s practice writing interview questions. Using the Take Notes Tool write write three questions for our rancher that will help us learn more about our research question, “Can grazing cattle be good for the environment and affordable for the consumer?” When you are finished, click on Check your Understanding to see three questions that I wrote.

Why did you choose to graze your cattle instead of feeding them grain? Do you have to charge more per pound to sell grass-fed beef than you would if you fed them grain? To which restaurants do you currently sell your beef?

CloseSurveys

Conducting a survey is another kind of primary research. Surveys can tell you what a large number of people think about a topic. Think of surveys as interviews with several people who aren’t necessarily experts in your subject but who might have an interest in it. For example, if you wanted to find out whether people would be willing to eat less meat if it would help protect the environment, you could conduct a survey.

Tips for an Effective Survey

- Choose the right people to survey. Do you want to know the opinion of students? Women only? Men only? People over 65 only? If we want to find out whether people would eat less meat to protect the environment, we need to survey people of any age or gender who regularly eat meat. Vegetarians will skew our results because they don’t eat meat at all.

- Decide how many people you will survey. If you survey too few people, you won’t be able to report any trends. If you survey too many, you will be overwhelmed by the amount of data.

- Decide how many questions you will ask. You don’t need to ask too many because your participants might get frustrated and not complete the survey.

As with interview questions, avoid bias and make your questions concise and simple. But in surveys you can ask closed-ended, yes/no questions.

Let’s practice what we’ve learned about surveys. Using the Take Notes Tool write write three questions for our rancher that will help us learn more about our research question, “Can grazing cattle be good for the environment and affordable for the consumer?” When you are finished, click on Check your Understanding to see three questions that I wrote.

I am going to survey 100 people on the Texas State University campus.

I am going to ask the following questions:

- Do you eat meat daily?

- Are you interested in doing more to protect the environment?

- Did you know that meat consumption contributes to air, soil, and water pollution?

- Would you be willing to give up eating meat one day a week to help protect the environment?

Observation

Observation is also a valuable type of primary research. Observations are typically part of science and social science experiments. The famous observer Jane Goodall spent years living with chimpanzees observing and recording their behavior. Your observations don’t have to involve changing your living arrangements to be effective, though!

How can you use observation as a research tool to help answer the question, “Can grazing cattle be good for the environment and affordable for the consumer?” What if you aren’t convinced that grazing cattle was better for the environment than cattle raised on a feedlot? It might be a good idea to arrange a few visits to ranches that raise cattle each way. You could see how each ranch handles issues related to the environment, such as disposing of cow waste, and moving cattle to different pastures to prevent erosion and depletion of the soil.

Conducting an Effective Observation

- Don’t intrude on the activities and behaviors you are observing.

- Take detailed notes.

- Record the date and exact times you arrive and leave.

- Observe on more than one occasion and try to visit at different times of day.

Let’s do a short activity to review what you know about primary and secondary research. Below is a chart with two columns, labeled “Primary Research” and “Secondary Research.” Underneath the chart is a kind of source. Drag each source to its correct column.

Taking Notes about Your Sources

As you begin finding the sources that you need for your research, you will need to record certain details about them. At the end of every research paper, you will need to include a bibliography page. This page lists details about the sources in your paper, such as author names, titles, page numbers, and more. It’s important that you have a system for taking notes about your sources. You will need them not only when you create your bibliography, but when you draft your paper as well.

I have created a note-taking document that you can print and use when you write your research paper. Click the link, and let’s look at this document together. You can either type into it or download and print it for this lesson. Notice that every page you print will have space for two sources. At the top, you should write your research question.

- For Description of source write the kind of source: book, article, or website.

- For Author write the names of the author or authors. If you don’t know who wrote it, write ’unknown.’

- Under Publication write the exact title of the book, journal, newspaper, magazine, or website.

- Under Publication date, write the date the book or article was published.

- Under Web address write the exact web address for the website. You want to be able to access this site again without searching for it, so be sure to write or cut and paste the entire address.

- Under Date accessed write the date you accessed the website.

- Under Page numbers write the page numbers with information that you want to paraphrase, summarize, or quote.

- Under Location of source write where you found the source. Did you find it at the school library? At the public library? This is especially important for books. If you don’t check the book out at the time you are evaluating it, you might want to find it later.

- Under Summary, quote, or paraphrase write what it is from the source you want to use.

This information should be enough to get you started when you write your first draft. You will need more for your bibliography, but it is better to worry about that when you know exactly which sources you will use. You will learn exactly how to document your sources in another lesson, “Documenting Sources and Writing a Bibliography/Works Cited.”

Let’s look more closely at the last section, “Summary, quote, or paraphrase.” These will be covered completely in the lesson, “Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting Source Material Accurately,” but here’s a quick discussion.

When you summarize, you restate the ideas of an entire source in a few sentences. A summary must be in your own words. If you use any words or phrases from the original source, you must put them in quotation marks. You might summarize a book, article, or website.

When you paraphrase, you take a passage from your source material and put it into your own words. Paraphrases are shorter than the original material. Quotations are exact words from the source set off with quotation marks. Whenever you use words that are not your own, you must set them off in quotes and identify the original author of those words. Quotations work best when the author has said something striking that you think your reader needs to see in the original wording.

For example, suppose I use the book In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto by Michael Pollan as a source. If I were to summarize the book, I would say that it is a book about how the American diet has come to rely on convenient, prepared foods that aren’t healthy and aren’t really as tasty as freshly-prepared foods. I might also like to paraphrase his introduction by writing that Pollan traces the shift in the American diet to the 1980s, when food manufacturers began marketing foods as “nutrients.” They started using science to convince us that their foods would lower our cholesterol or prevent diabetes better than the foods we prepared ourselves. If I were to quote Pollan, I might write that Pollan’s solution to our unhealthy eating habits is simply this: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” I would use that quote because it is an elegant, concise summary of his position.

Test Your Understanding

Complete the following steps to take a quiz that tests your understanding of this topic.

- Click on the link below. The quiz will open in a new window.

- When you have completed the quiz, click the Submit button.

- Close the window to return to this page.

- To review your test results, click the Tests/Quizzes button in the left-hand Epsilen navigation menu to open the Tests/Quizzes page.

- Under Past Tests/Quizzes locate the test for Research: Module 1: Lesson 2 and click on the magnifying glass icon to view your results.

Please Note: Question/answer choices periodically appear out of order onscreen. This is a known program bug within Epsilen and is currently being addressed.

Click here to take the quiz on this lesson.

Click here to take the quiz on this lesson.Resources

Faigley, Lester. The Penguin Handbook. New York: Pearson Education, Inc., 2003.

Pollan, Michael. In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto. New York: Penguin, 2008.

“Purdue Online Writing Lab.” Purdue University. http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/.