Source: Reading-jester-q75-760x753, Bill Nye, Wikimedia

Reading a novel or story with an unreliable narrator can be one of the most interesting (and sometimes maddening) experiences in reading fiction. An unreliable narrator is just what you might expect from its name: a narrator whose version of events may or may not be exactly what happened. This idea can be perplexing to say the least: that a fictional character, someone dreamed up by an author sitting at a computer or writing on a legal pad, could be lying, misrepresenting, or misunderstanding what happened in a story in the course of telling it.

Our first impulse when reading fiction is to take what is on the page at face value. It’s not like this character made of words on a flat page has an agenda, is it? Yet those words didn’t just appear on the page. A writer put them there, and an unreliable narrator is a literary device often used by a writer who has an agenda. Stories and novels with an unreliable narrator are often told from the first-person point of view.

Types of Unreliable Narrators

These are the main types of unreliable narrators and some tones that are associated with them. If you suspect you are reading an unreliable narrator, analyze the tone of the narration for clues.

Young narrator

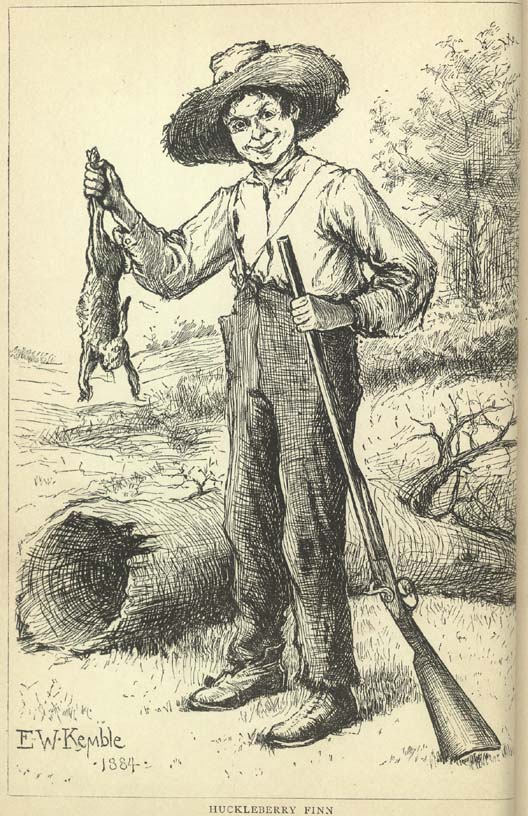

Young narrators are sometimes unreliable because they are too young or immature to understand the scenes they are witnessing. If the narrator seems childlike, immature, or naive, especially in the face of adult situations, the narrator might be unreliable. Let’s look at an example from Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Source: Huckleberry-finn-with-rabbit, Edward Winsor Kemble

. . . Jim, had a hair-ball as big as your fist, which had been took out of the fourth stomach of an ox, and he used to do magic with it. He said there was a spirit inside of it, and it knowed everything. So I went to him that night and told him pap was here again, for I found his tracks in the snow. What I wanted to know was, what he was going to do, and was he going to stay? Jim got out his hair-ball and said something over it, and then he held it up and dropped it on the floor. It fell pretty solid, and only rolled about an inch. Jim tried it again, and then another time, and it acted just the same. Jim got down on his knees, and put his ear against it and listened. But it warn’t no use; he said it wouldn’t talk. He said sometimes it wouldn’t talk without money. I told him I had an old slick counterfeit quarter that warn’t no good because the brass showed through the silver a little, and it wouldn’t pass nohow, even if the brass didn’t show, because it was so slick it felt greasy, and so that would tell on it every time. (I reckoned I wouldn’t say nothing about the dollar I got from the judge.) I said it was pretty bad money, but maybe the hair-ball would take it, because maybe it wouldn’t know the difference.

Huck Finn is one of the best-known examples of an unreliable narrator. He is young, superstitious, and uneducated. He believes in magic and signs and is sometimes unable to understand the reality of what he is experiencing. Before the excerpt above, Huck has found a footprint in the snow: the heel of a boot that has a cross made of nails embedded in it to ward off the devil. Huck recognized the footprint as belonging to his father, Pap, an abusive drunk. So, he has gone to Jim with the hope that Jim can tell him what Pap’s intentions might be. The fact that Huck believes that Jim can use magic to predict Pap’s actions gives us some insight into Huck’s understanding of how the world works. Huck’s belief that he can cheat the “hair ball” with fake money also illustrates his immaturity and his unreliability as a narrator.

Mentally ill or confused narrator

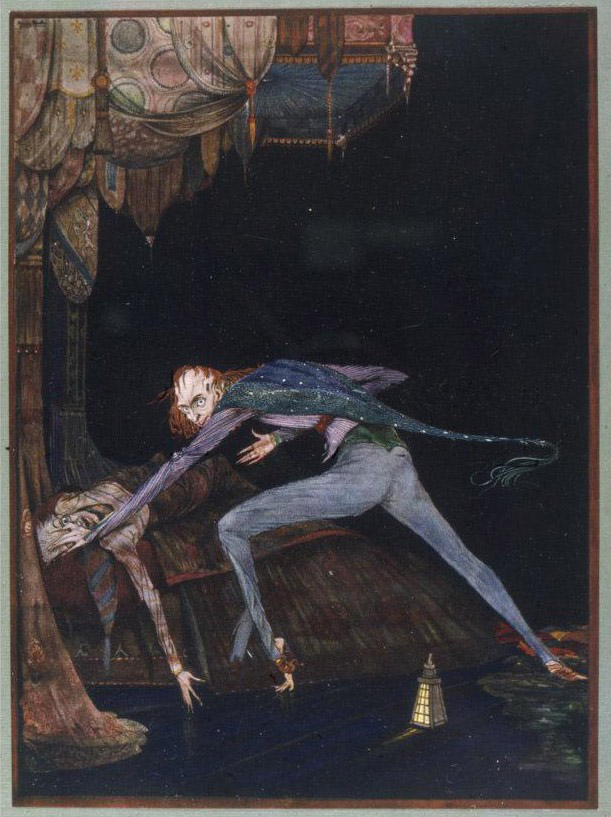

Narrators who are mentally ill or mentally challenged may lack the ability to assess the situations they are relating. If the narrator seems befuddled, depressed, or contradictory, the narrator might be unreliable. An example of this type of narrator can be found in the Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.”

Source: Clarke-TellTaleHeart, Harry Clarke, Wikimedia

True! nervous, very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why WILL you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses, not destroyed, not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How then am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily, how calmly, I can tell you the whole story.

It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain, but, once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! Yes, it was this! One of his eyes resembled that of a vulture—a pale blue eye with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me my blood ran cold, and so by degrees, very gradually, I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye for ever.

From the first sentence of the story, the narrator claims that he is not crazy, but then he immediately tells us that he “heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. . . . [and] many things in hell.” In the next paragraph, he decides to kill an old man, whom he claims to love, because of the man’s pale blue eye. Clearly, the narrator is mad, and his perceptions of what is real and what is not are completely false.

A criminal narrator

Narrators who tell about a crime they committed will likely be unreliable because it is in their best interest to keep the true facts of the story a mystery. These narrators are usually defensive, secretive, or aggressive in deflecting suspicion. On the other hand, they might be manipulative in trying to justify their actions. An example of this is another Poe story: “The Cask of Amontillado.” In this story, Montressor, the narrator, admits to murdering Fortunato by sealing him inside a wall. However, because Montressor was judge, jury, and executioner, we can’t know for sure what really happened. Let’s look at an excerpt.

Source: Untitled, DuSty FaiRy TaLe, Flickr

The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could, but when he ventured upon insult, I vowed revenge. You, who so well know the nature of my soul, will not suppose, however, that I gave utterance to a threat. AT LENGTH I would be avenged; this was a point definitively settled—but the very definitiveness with which it was resolved precluded the idea of risk. I must not only punish, but punish with impunity. A wrong is unredressed when retribution overtakes its redresser. It is equally unredressed when the avenger fails to make himself felt as such to him who has done the wrong.

It must be understood that neither by word nor deed had I given Fortunato cause to doubt my good will. I continued as was my wont, to smile in his face, and he did not perceive that my smile NOW was at the thought of his immolation.

Montressor tells us that anyone who truly knows him would understand that he would never alert Fortunato to his imminent danger. Montressor goes into great detail when he brags about how he lured Fortunato into the cellar where Montressor walled him in, but he never provides any information that allows us to decide whether or not his revenge was justified. He tries to manipulate the reader into believing his story by withholding information.

Context Clues for Identifying the Unreliable Narrator

Source: detective con lupa, Pablo lizard, Flickr

Here are some clues that should make you suspect an unreliable narrator.

- Sudden shifts in tone

- Admission of mental illness

- Youth and inexperience

- Admission of wrongdoing

- Inconsistent storytelling

Let’s read and analyze some excerpts from the story “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. You can read the entire story here, but this is not required. The narrator of “The Yellow Wallpaper” is a young woman who is suffering from some sort of mental breakdown. She and her husband are renting a house in the country so that she can rest and recuperate. Here’s a passage from the beginning of the story.

John laughs at me, of course, but one expects that in marriage. John is practical in the extreme. He has no patience with faith, an intense horror of superstition, and he scoffs openly at any talk of things not to be felt and seen and put down in figures. John is a physician, and perhaps—(I would not say it to a living soul, of course, but this is dead paper and a great relief to my mind) — perhaps that is one reason I do not get well faster. You see he does not believe I am sick!

From the very beginning, the narrator seems angry and frustrated. She states that perhaps her husband is the reason she doesn’t get well; he doesn’t believe she is sick. She says that he is a physician, so we also have to wonder, “Is she really sick?”

As the narrator describes where they are staying, “a big, airy room, the whole floor nearly, with windows that look all ways, and air and sunshine galore,” the setting sounds like it might be a nice place to spend some time–but then she begins to describe the wallpaper.

The paint and paper look as if a boys’ school had used it. It is stripped off—the paper—in great patches all around the head of my bed, about as far as I can reach, and in a great place on the other side of the room low down. I never saw a worse paper in my life.

One of those sprawling flamboyant patterns committing every artistic sin.

It is dull enough to confuse the eye in following, pronounced enough to constantly irritate and provoke study, and when you follow the lame uncertain curves for a little distance they suddenly commit suicide—plunge off at outrageous angles, destroy themselves in unheard of contradictions. The color is repellent, almost revolting; a smouldering unclean yellow, strangely faded by the slow-turning sunlight. It is a dull yet lurid orange in some places, a sickly sulphur tint in others.

The description is unflattering and obsessive, and the line about the “lame uncertain curves” that “suddenly commit suicide” makes me again wonder about the reliability of the narrator. Is it a nice, airy, sunny room? Is the wallpaper so incredibly ugly that it overshadows the virtues of the room? The narrator’s tone constantly shifts from neutral to anxious and angry. When the narration suddenly changes tone or makes you ask a lot of questions about what the narrator really means, you are dealing with an unreliable narrator.

Reread the excerpt above, using the your notes to record additional details the author uses that make you think that the narrator is unreliable. When you are finished, check your understanding to see a possible response.

All of the narrator’s descriptions of the room contradict each other. This makes it very difficult for the reader to form an accurate picture of the room, but it tells us a lot about the reliability of the narrator. How can we rely on her assessment of her situation if she can’t make an accurate and coherent description of the room?

She describes the wallpaper as “committing every artistic sin.” This statement is very dramatic and very difficult to picture. What exactly does this mean?

She also says that it is “dull enough to confuse the eye” but also “pronounced enough to constantly irritate and provoke study.” This contradiction suggests a person who is very agitated and can’t focus but rather keeps shifting between contradictory perceptions.

The orange of the wallpaper is both “dull” and “lurid.” Lurid is an interesting word choice because it suggests a tone of disgust. She uses other words with the same connotation, like “sickly,” “revolting,” and “repellent.”

These details tell us she is unreliable because they are so inconsistent.

As we read, the narrator becomes more and more inconsistent and unbalanced until finally she is so unhinged that she is crawling around the nursery, ripping the wallpaper off the walls. When her husband goes to her in the nursery, he passes out from the shock of seeing her condition—or so she tells us!