Source: Right and Wrong, Essg, Flickr

We often describe decisions as being “black and white,” meaning that there is a distinctly right and a distinctly wrong choice. Yet, as we have discussed, sometimes supposedly good people do bad things for the “right” reasons. This is also the case in literature. For this reason, to identify a moral dilemma in literature, you often need to understand the context of the piece because morals and ethics change over time.

Let’s think about slavery for a moment. Most people in most cultures agree that a person should not own another person. (I am saying “most” here because, unfortunately, slavery still exists in some places.) However, this is not true throughout all the settings and time periods covered by the literature of the United States. Slavery was abolished 150 years ago, and Americans agree that the period in which slavery was considered legally and morally acceptable was a terrible part of our history.

Huckleberry Finn

Slaves were punished and sometimes killed for trying to escape, and whites were punished for trying to help escaped slaves. Moral certainty was shaky on both sides of the issue.

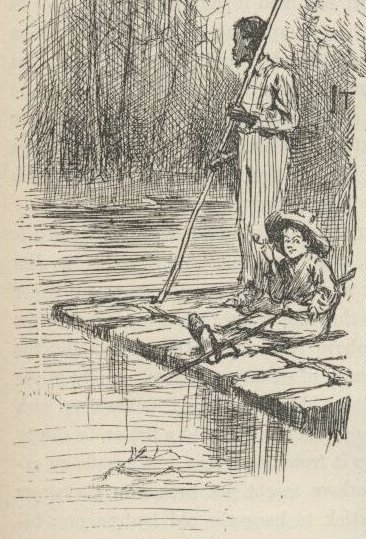

Let’s take a look at The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain. In this book, Huck Finn fakes his death and runs away to escape his abusive father. He takes off down the Mississippi River on a raft and hides on Jackson’s Island. After a few days, Huck runs into an escaped slave named Jim. Jim tells Huck that he ran away because he was worried that his owner Miss Watson was planning to sell him down the river. Jim makes Huck promise not to tell anyone he has seen him. Huck says:

Source: Huck and jim on raft, E.W.

Kemble, Wikimedia

People would call me a low-down Abolitionist and despise me for keeping mum – but that don't make no difference. I ain't a-going to tell, and I ain't a-going back there, anyways. So, now, let's know all about it.

No one today would think of an Abolitionist as “low-down.” Quite to the contrary, abolitionists are regarded as heroes for doing what they knew to be right above their own self-interests. In the days of Huck Finn, however, harboring a runaway slave posed a dilemma.

This next excerpt comes later in the novel. Huck has decided to write the Widow Douglas to confess that he knows where Jim is. Huck decides that he will pray for forgiveness for not having told the Widow earlier about Jim’s escape. He tries and tries but the prayer won’t come.

Source: TOM SRP 2011 JIM AND HUCK, hcplebranch, Flickr

I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life, and I knowed I could pray now. But I didn't do it straight off, but laid the paper down and set there thinking — thinking how good it was all this happened so, and how near I come to being lost and going to hell. And went on thinking. And got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me all the time: in the day and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storms, and we a-floating along, talking and singing and laughing.

But somehow I couldn't seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind. I'd see him standing my watch on top of his'n, 'stead of calling me, so I could go on sleeping; and see him how glad he was when I come back out of the fog; and when I come to him again in the swamp, up there where the feud was; and suchlike times; and would always call me honey, and pet me and do everything he could think of for me, and how good he always was; and at last I struck the time I saved him by telling the men we had smallpox aboard, and he was so grateful, and said I was the best friend old Jim ever had in the world, and the only one he's got now; and then I happened to look around and see that paper.

It was a close place. I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a-trembling, because I'd got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself: “All right, then, I'll go to hell”— and tore it up.

Ironically, this chapter is sometimes titled “You Can’t Pray A Lie.” Today we can’t imagine that Huck would pray for forgiveness for not turning in Jim to the authorities. What Huck finds is that he really can’t pray a lie because Jim has become his friend. Huck is transforming from a person who sees Jim as less than human to someone who sees him as a fellow human being and a friend.

Within the context of the times, Huck’s dilemma is in the gray area. He loves Jim and doesn’t want him to be a slave on an unknown farm; he doesn’t want Jim to be a slave at all. However, he also worries what will happen to his own reputation once everyone back home finds out he helped Jim escape. Huck finally decides that Jim's being free is worth more than his own reputation and even his own soul. Again, the irony is evident to us. Huck thinks about going to hell for what we today in the twenty-first century see as doing the right thing.

Caleb's Crossing

Source: Squanto, NormanEinstein, Wikimedia

Source: Massasoit, KC MO – detail, Cyrus E. Dallin,

Wikimedia

The novel Caleb’s Crossing is about a young American Indian boy named Caleb who faces giving up his previous way of life for another.

The following excerpt occurs before Caleb leaves for Cambridge University. Bethia, the Puritan narrator and friend to Caleb, has agreed to indenture herself there so her brother can attend Cambridge too. Caleb tries to talk her out of doing so. Read through the passage once and then read through it again and click on the sentence that contains the dilemma that Caleb faces. Remember the person narrating is Bethia. If you choose correctly, the sentence will highlight. Next, click the sentence in which Caleb makes his decision. Again, if you choose correctly, the sentence will highlight.

[Caleb] lifted a fistful of sand and let if fall through his fingers. “You ask why I eat with you, learn your prayers. Why I study to hate all that I once loved. Put your ear to the sand. You will hear my reason.”

I tilted my head, puzzled.

“Can you not hear? Boots, boots, and more boots. The shore groans under the weight, and yet more come. They crush the life from us.”

“But, Caleb,” I said. “This land – I mean the mainland – they say it is a vast wilderness – there is room and to spare even when we come many thousands...”

He scooped up another handful of sand and stared at each grain as it fell through his fingers. “You are like these. Each a trifling speck. A hundred, many hundreds – what matter? Cast them into the air. You cannot even find them when they land upon the ground. But there are more grains than you can count. There is no end to them. You will pour across this land, and we will be smothered. Your stone walls, your dead trees, the hooves of your strange beasts trampling the clam beds. My uncle sees these things, here and now. And in his trance, he sees that worse is coming. Your walls will rise everywhere until they shut us out. You will turn the land upside down with your ploughs until all the hunting grounds are gone. This, and more, my uncle sees.” Caleb slapped his hand down upon the sand, then, he drew it into a fist. “And yet he refuses to see that God prospers you, and protects you, and keeps from you the sicknesses against which his powers are as nothing. So, this do I see: we must find favor with your God, or die. That, Storm Eyes, is why I came to your father.” His expression was grim. I wanted to reach for his hand, offer some comfort. But I did not. I just sat there, wordless, until he spoke again.

“Life is better than death. I know this. [My uncle] says it is the coward’s talk. I say it is braver, sometimes to bend.”

He turned to me, “That is why I will go now to this Latin school, and the college after, and if your God prospers me there, I will be of use to my people, and they will live.

In this excerpt and the one from Huckleberry Finn, you see characters face very American dilemmas; however, one protagonist is the oppressor and the other is the oppressed. Caleb is the victim in a world being overtaken by European migration.

Again, using a Venn Diagram, drag the following statements about the two excerpts into their proper places to compare them.

Looking at your Venn Diagram, what can you say about the moral dilemmas and the decisions made by Huck and Caleb? Consider this question before moving on to the next section.