Part 1 - TEKS Glossary and Syllabus

- Lesson title: Major Literary Periods and The Historical/Cultural Events That Influence(d) Writers

- Student-friendly summary of lesson: You will be able to read a text and identify the literary time period in which it was written and understand the significance of that time period.

- At least 3-5 key words in the lesson, including their definitions from the TEKS Glossary: Theme, Purpose, Diction, Parallel structure, Primary source, Style, Mythic literature, Allusion, Aphoristic, Tone, Tract.

Introduction

In this lesson we will study the historical periods of American literature. A nation’s literature is often studied in chronological order because of how deeply historical events influence writers of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. At the conclusion of this lesson, you should be able to read a text, identify the literary time period in which it was written, and understand the significance of that time period. You should also be able to analyze how the style, tone, and diction of a text advance the author’s perspective and purpose. The author’s purpose will often be connected to the historical events of the time.

The earliest literature in our country was that of the Native Americans, whose oral tradition included songs, tales, and mythic literature passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth. The written tradition began with the arrival of Europeans who, although influenced by the writers of the continent from which they came, would eventually create an original American literature.

You will learn how literature produced in America is linked to events such as colonization, the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and the Industrial Revolution. You will see how American literature has changed over time because of historical influences. Keep in mind that various literary critics assign different names and years to the movements in American literature.

Lakota storyteller, Anne Bradstreet, Ben Franklin, Edgar Allen Poe, Emily Dickinson, Jack London, E. E. Cummings,

Lakota storyteller, Anne Bradstreet, Ben Franklin, Edgar Allen Poe, Emily Dickinson, Jack London, E. E. Cummings, Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison. © 2011 by IPSI. Photo of Toni Morrison from American Library Association.

Colonial and Revolutionary Periods

(1607–1830)

The Colonial Period

Study the chart of the Colonial period (the Age of Faith), 1607–1765. It lists genres and authors along with their themes and literary advances. Then read the excerpts from some of the examples. After you finish reading, you will be asked to answer questions that require you to draw conclusions about the literature of the time.

|

Genres and Authors |

Styles and Themes |

Literary Advances |

|---|---|---|

|

Histories

|

|

|

|

Sermons

|

|

|

|

Journals

|

||

|

Documents |

|

|

|

Poetry

|

|

Excerpt from Anne Bradstreet’s “Upon the Burning of Our House”

Raise up thy thoughts above the sky

That dunghill mists away may fly.

Thou hast an house on high erect,

Framed by that mighty Architect,

With glory richly furnished,

Stands permanent though this be fled

It’s purchased and paid for too

By Him who hath enough to do.

A price so vast is unknown

Yet by His gift is made thine own;

There’s wealth enough, I need no more

Farewell, my pelf,1 farewell my store.

The world no longer let me love,

My hope and treasure lies above.

1. pelf n. : Money or wealth regarded with contempt.

Excerpt from William Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation

There was a proud and very profane young man, one of the seamen, of a lusty, able body, which made him the more haughty; he would always be condemning the poor people in their sickness and cursing them daily . . . and did not let to tell them that he hoped to help to cast half of them overboard before they came to the journey’s end . . . But it pleased God before they came half seas over, to smite this young man with a grievous disease, of which he died in a desperate manner, and so was himself the first that was thrown overboard.

Now answer these questions about what you’ve read. The correct responses will offer additional insights about the literature of the Colonial period.

- The literature of the Colonial period was primarily nonfiction.

- The Puritans did not consider education especially important.

- Strong religious beliefs are reflected in the writing of the Colonial period.

- The tone of most writing during the Colonial period was serious; the author’s purpose was usually to inform, to glorify God, or to do both.

Correct! Histories, journals, and sermons—all nonfiction forms—constitute the literature of this period. Bradstreet’s poetry is an exception. In addition, much of the writing was private (journals, diaries). Even Bradford’s account of the Pilgrim experience was not intended to be published, but to serve as a family record and tribute to the founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

CloseTry again.

CloseTry again.

CloseCorrect! The establishment of Harvard University indicates that the Puritans did value education. A literate population was important so that the faithful could read the Bible.

CloseCorrect! Bradstreet seeks comfort in a heavenly home when her earthly one burns. Bradford sees the hand of God in the death of the “proud and very profane” sailor aboard the Mayflower.

CloseTry again.

CloseCorrect! The very title, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” suggests the seriousness of the writing. The purpose of the writing was not to entertain.

CloseTry again.

CloseThe Revolutionary Period

Study the chart of the Revolutionary period (also known as the Enlightenment or the Age of Reason), 1765–1830. William Harmon, author of A Handbook to Literature, divides the period into two parts: 1765–1790 (the “Revolutionary Age”) and 1790–1830 (the “Federalist Age”).

After you finish reading, you will be asked to answer questions that require you to draw conclusions about the literature of the time.

|

Genres and Authors |

Styles and Themes |

Literary Advances |

|---|---|---|

|

Autobiographies

|

|

|

|

Pamphlets

|

|

|

|

Political Tracts

|

|

|

|

Speeches

|

||

|

Reference Books

|

Students of American history and literature value the pamphlets and political tracts of the Revolutionary period as primary source documents. The same is true of the histories, diaries, and journals of the Colonial period. This is a page from Common Sense, published in 1776 by Thomas Paine.

Read these excerpts from Revolutionary literature. Be sure to read the pop-up comments, which identify aspects of style and other insights about the literature of this period.

Excerpts from Patrick Henry’s “Speech in the Virginia Convention,” 1775

- Is this the part of wise men, engaged in a great and arduous struggle for liberty?

- I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided, and that is the

lamp of experience. - Suffer not yourselves to be betrayed with a kiss.

- Sir, we have done everything that could be done to avert the storm which is now coming on. We have petitioned; we have remonstrated; we have supplicated; we have prostrated ourselves before the

throne . . . - Our chains are forged! Their clanging may be heard on the plains of Boston! The war is inevitable—and let it come! I repeat it, sir, let it come!

- I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

Excerpt from the Declaration of Independence

written by Thomas Jefferson

“He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burned our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.”

Now answer these questions about what you’ve read. The correct responses will offer additional insights about the Revolutionary period.

- The writing in the Colonial period was often intended to be private, while most of the works in the Revolutionary period were designed to be public.

- The purpose of much of the literature of this period was to entertain the growing American population.

- The literature of the Revolutionary period was produced by professional writers.

Correct! The founding fathers wanted their opinions and arguments to be widely heard in England and America.

CloseTry again.

CloseTry again.

CloseCorrect! Henry and Jefferson spoke and wrote to persuade.

CloseTry again.

CloseCorrect! Although these statesmen produced excellent writing, they were not usually professional writers.

CloseRomanticism and the

“American Renaissance” (1830–1865)

Romanticism

You have seen that the literature of the Colonial and Revolutionary periods was primarily nonfiction composed by the early settlers and founding fathers to inform and persuade. During the Romantic period (roughly a half century before the Civil War), literature as a fine art emerged, and authors sought to entertain their audiences. As a literary movement, Romanticism began in Europe. American writers, although they were influenced by European Romanticism, eventually developed a distinctive American Romanticism with unique characteristics.

Watch “Romanticism in the American Short Story.” Then answer the multiple-choice questions. Write your answers using your Take Notes Tool. When you are finished, check your understanding

- The Romantic writers had an interest in things that—

- A. could be proven scientifically.

- B. were beyond the realm of science and logic.

- C. involved romantic love.

- D. reflected their deep faith in God.

- The Romantic writers were interested in—

- A. psychology and the forces that lurk deep in the human psyche.

- B. eternal salvation and how man could achieve it.

- C. the rights of American citizens.

- D. God and the Devil.

- Many Romantic writers focused on—

- A. firsthand accounts of life on the American frontier.

- B. actions Americans must take to avoid the wrath of God.

- C. biblical allusions.

- D. gothic imagery.

- All of the following can be classified as Romantic writers except—

- A. Edgar Allan Poe

- B. Nathaniel Hawthorne

- C. Benjamin Franklin

- D. Washington Irving

B is the correct answer. A is incorrect since it describes the interests of the Revolutionary writers, not the Romantic writers. D pertains to the Colonial period. C is incorrect because romantic love is not the focus of Romanticism.

CloseA is the correct answer. B and D are incorrect because they describe Colonial writing. Answer C is wrong because rights were more the concern of Revolutionary writers.

CloseD is the correct answer. Gothic imagery was covered in the video you watched. Colonial writers would have been more likely to focus on B and C. Romantics were interested in the supernatural, but not creating religious literary works.

CloseC is the correct answer. You should have remembered Benjamin Franklin as a nonfiction writer from the Revolutionary period. Poe, Hawthorne, and Irving all contributed to the growing body of unique American literature.

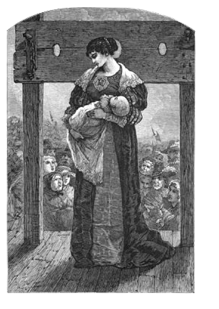

Close Drawing of Hester Prynne on the scaffold with Pearl, from The Scarlet Letter

Drawing of Hester Prynne on the scaffold with Pearl, from The Scarlet Letter - Exotic settings—past or present

- Emphasis on the beauty and inherent goodness of nature in contrast

to the corruption that could be found in human society - Mysterious or supernatural elements

- Commitment to individualism

The “American Renaissance” (including Transcendentalism)

The "American Renaissance" is often considered synonymous with American Romanticism. In American literature, much poetry and prose was produced during this period before the Civil War. Transcendentalism (with its reliance on intuition and conscience) was an important influence on many writers.

Study the chart of the Romantic period and the "American Renaissance." You will notice that writers from these periods overlap. After you have studied the chart, you will see poems and excerpts from essays written during this period.

|

Genres and Authors |

Styles and Themes |

|---|---|

|

Short Stories

|

|

|

Poetry

|

|

|

Novels

|

|

|

“New” American Poetry

|

|

|

Essays

|

|

Now read “The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls,” a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882). Longfellow was one of the Fireside Poets, so called because families often read their poetry around the fireplace in the evening. This poem, which Longfellow wrote toward the end of his life, is about a traveller through life. Notice the regular rhyme pattern.

The tide rises, the tide falls,

The twilight darkens, the curlew calls;

Along the sea-sands damp and brown

The traveller hastens toward the town,

And the tide rises, the tide falls.

Darkness settles on roofs and walls,

But the sea in the darkness calls and calls;

The little waves, with their soft, white hands,

Efface the footprints in the sands,

And the tide rises, the tide falls.

The morning breaks; the steeds in their stalls

Stamp and neigh, as the hostler calls;

The day returns, but nevermore

Returns the traveller to the shore,

And the tide rises, the tide falls.

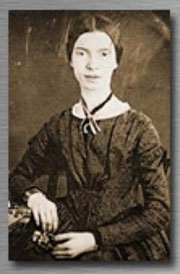

Unlike the Fireside Poets, Emily Dickinson (1830–1886) does not fit into any particular category. Note her use of slant rhyme, also known as off rhyme, in contrast with Longfellow’s exact rhymes. Some of her other trademarks include creative capitalization and the frequent use of dashes.

I never saw a Moor—

I never saw the Sea—

Yet know I how the Heather looks

And what a Billow1 be.

I never spoke with God

Nor visited in Heaven—

Yet certain am I of the spot

As if the Checks2 were given—

1 Billow: large wave

2 Checks: Colored seat checks indicating the destinations of passengers on a train after their tickets have been collected.

Photograph of Emily Dickinson,

Photograph of Emily Dickinson, 1846 or 1847, by William C. North

In this poem, we see one of the important characteristics of American Romanticism: the idea of finding truth through intuition and imagination. In the second stanza Dickinson conveys her certainty in a God and heaven despite never having experienced them.

Walt Whitman, July 1854, engraving by Samuel Hollyer

Walt Whitman, July 1854, engraving by Samuel HollyerWalt Whitman, sometimes considered America’s first modern poet, is another example of the poetry of the American Renaissance. Listen to the audio of “I Hear America Singing.” Listen especially for the occupations Whitman includes.

Whitman celebrated the unique “song” of each of the following: mechanics, carpenters, masons, boatmen, deckhands, shoemakers, hatters, woodcutters, ploughboys, mothers, young wives, and girls sewing or washing. His “catalog” emphasizes the equality of people regardless of their line of work.

Excerpts from “Self-Reliance” by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

Watch the video based on “Self-Reliance.” Hint: You may have to watch the video more than once to infer some of Emerson’s ideas. Then answer the questions that follow.

- Emerson urges you to imitate others in your quest for truth.

- As individuals we know what is best for us.

- Emerson advocates nonconformity.

- Nature is important to the well-being of mankind.

Try again.

CloseCorrect! The title alone suggests that you should trust yourself rather than rely on others in forming your opinions and beliefs.

CloseCorrect! Emerson urges us to "detect and watch that gleaming light which flashes across [our] mind[s] from within." Note the emphasis on both intuition and individualism here.

CloseTry again.

CloseCorrect! He says “My life is for itself and not for a spectacle,” and “I must be myself.”

CloseTry again.

CloseCorrect! Emerson says that “man cannot be happy and strong until he lives in nature.”

CloseTry again.

CloseRealism, Naturalism,

and Regionalism (1865–1915)

Realism

Romanticism receded and realism emerged as a result of the Civil War, advances in transportation and communication (railroads, the telegraph), industrialization (including a movement from farm to city), European immigration, and population growth. Writers began to depict the hardships Americans experienced in war and in earning a living. According to William Harmon, author of A Handbook to American Literature, realists took as the subjects of their writing “the common, the average, the everyday.” They concentrated on “the immediate, the here and now.”

The editors of Prentice Hall Literature: The American Experience distinguish the three “isms” of the period in this way: “Realism attempted to present ‘a slice of life,’ whereas Naturalism went one step further, showing life as the inexorable working out of natural forces beyond our power to control. Regionalism, in contrast, was in some ways a blending of Realism and Romanticism. It emphasized locale, or place, and the elements that create local color—customs, dress, speech, and other local differences.”

Study the chart of the Realistic period. Then read samples from this period below the chart.

|

Genres and Authors |

Styles and Themes |

Literary Advances |

|---|---|---|

|

Novels

|

|

|

|

Short Stories

|

|

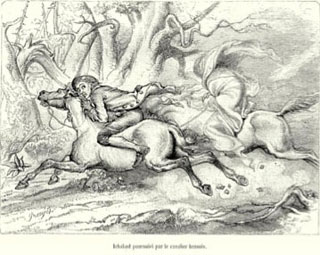

Illustration from “To Build a Fire,” by Jack London. Tom Vincent struggles with a dying campfire.

Illustration from “To Build a Fire,” by Jack London. Tom Vincent struggles with a dying campfire.Excerpt from Jack London’s “To Build a Fire”

At the man’s heels trotted a dog, a big native husky, the proper wolf dog . . . The animal was depressed by the tremendous cold. It knew that it was no time for traveling.

It experienced a vague but menacing apprehension that subdued it and made it slink along at the man’s heels, and that made it question eagerly every unwonted movement of the man as if expecting him to go into camp or to seek shelter somewhere and build a fire. The dog had learned fire, and it wanted fire . . .

The dog, like the man, faces natural forces beyond its control, but seems to recognize instinctually the necessity of building a fire.

The Modern (1914–1945)

and Postmodern (1945–Present) Periods

Modernism

Note that the Modern period spans the years between World War I and World War II, both of which brought about great changes in our country. Keep in mind that this period included the Jazz Age also known as the Roaring Twenties, and the Great Depression of the 1930s.

In some ways, the Modern period was a response to the Realist literature that came before it—where Realists focused on slices of life and common, everyday experience, Modernists often focused on individualism and themes of the unconscious. Like abstract painters like Pablo Picasso or Morgan Russell (below) and surreal painters like Salvador Dali, Modernists looked beyond mundane "kitchen sink realism" toward a world that was at times distorted, symbolic, and even mythical.

|

Genres and Authors |

Styles and Themes |

|---|---|

|

Poetry

|

|

|

Novels

|

|

|

Poetry

|

|

|

Drama

|

|

|

Short Stories

|

|

As you read the following excerpts by poets Carl Sandburg and E. E. Cummings, think about how they look at "Realist" subject matter, but reinterpret it as modern poets. Study the chart and read the excerpts that follow.

Excerpt from Carl Sandburg’s “Chicago”

Train yard © 2010

Train yard © 2010Hog Butcher for the World,

Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,

Player with Railroads, and the Nation’s Freight Handler;

Stormy, husky, brawling,

City of the Big Shoulders:

The poet is writing about workers—butchers, train drivers, freight shippers. At the same time, he applies those qualities to the city of Chicago, as if it was a giant that did the same work for the world.

CloseExcerpt from E.E. Cummings’s

“anyone lived in a pretty how town”

E. E. Cummings

E. E. Cummingsanyone lived in a pretty how town

(with up so floating many bells down)

spring summer autumn winter

he sang his didn’t he danced his did.

“Anyone” might refer to everyman since the poem recounts the lives of the residents of a nameless town, thereby suggesting universality.

CloseIn the following passage from F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, narrator Nick Carraway describes a party he attends at the home of the immensely wealthy Jay Gatsby during the summer of 1922. His description reveals the excesses of the 1920s, which will come to a crashing (pun intended) end in 1929. The passage also hints at Gatsby's alienation and loneliness despite the fact that he has apparently achieved the American dream of material success.

Excerpt from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby

F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1936

F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1936At least once a fortnight a corps of caterers came down with several hundred feet of canvas and enough colored lights to make a Christmas tree of Gatsby’s enormous garden. On buffet tables, garnished with glistening hors d’oeuvre, spiced baked hams crowded against salads of harlequin designs and pastry pigs and turkeys bewitched to a dark gold. In the main hall a bar with a real brass rail was set up, and stocked with gins and liquors and with cordials so long forgotten that most of his female guests were too young to know . . .

I believe that on the first night I went to Gatsby’s house I was one of the few guests who had actually been invited. People were not invited—they went there. They got into automobiles which bore them out to Long Island and somehow they ended up at Gatsby’s door. Once there they were introduced by somebody who knew Gatsby and after that they conducted themselves according to the rules of behavior associated with amusement parks. Sometimes they came and went without having met Gatsby at all . . .

Postmodernism

Study the chart of the Postmodern period (1945–present). The term “postmodernism” refers to a number of literary movements, some of which build on the Modernists, some of which reacted against them. Two experimental forms worth noting are magical realism (style in which magical elements are blended in with a realistic setting, for example Toni Morrison’s Beloved) and creative nonfiction (nonfiction which uses many of the techniques of fiction, for example Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood). A sampling of other styles and themes appears in the chart below.

|

Genres and Authors |

Styles and Themes |

|---|---|

|

Drama

|

|

|

Novels

|

|

|

Autobiography

|

|

|

Poetry

|

|

Morgan Russell, Cosmic Synchromy (1913-14)

Morgan Russell, Cosmic Synchromy (1913-14) Your Turn

Use this activity to review selections from the past 400 years of American writing. Select a literary period from the time line, read the passage, and mouse over the name of the period for more information.

Resources

Resources Used in This Lesson: Bibliography

Bradford, William. History of ‘Plimoth Plantation.’ Reprint of the Boston edition, Project Gutenberg, 2008. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/24950/24950-h/24950-h.htm.

Bradstreet, Anne. “Upon the Burning of Our House.” Prentice Hall Literature: The American Experience. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1989.

Bryant, William Cullen. “Thanatopsis.” Adventures in American Literature. Pegasus Edition. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

Cummings, E.E. The United States in Literature. Glenview, Illinois: Scott Foresman, 1989.

Dickinson, Emily. “I never saw a Moor." Prentice Hall Literature: The American Experience. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1989.

Edwards, Jonathan. Prentice Hall Literature: The American Experience. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1989.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. “Self Reliance.” YouTube video, 2:04. Posted December 29, 2009. http://www.youtube.com/user/ajhande#p/a/u/2/OV5wcj3hbMc.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. New York: MacMillan, 1992.

Harmon, William. A Handbook to Literature. 10th Edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

Hennessy, David V. “Romanticism in the American Short Story.” YouTube video, 2:06. Posted December 22, 2009. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4mSrUTcbGM.

Henry, Patrick. “Speech in the Virginia Convention.” Prentice Hall Literature: The American Experience. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1989.

Hughes, Langston. “I, too, sing America.” The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. New York: Knopf, 1994.

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. “The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls.” The Complete Poetical Works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1902. Project Gutenberg e-Book. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1365/pg1365.html.

London, Jack. “To Build a Fire.” Adventures in American Literature. Pegasus Edition. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

Mayflower Compact, The. Cape Cod, MA. 1620. http://www.pilgrimhall.org/compact.htm.

Paine, Thomas. The Crisis, Number I. Prentice Hall Literature: The American Experience. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1989.

Plath, Sylvia. “Metaphors.” Literature: An Introduction to Reading and Writing. Edited by Edgar V Roberts and Henry E. Jacobs. 5th Edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1998.

Sandburg, Carl. “Chicago.” The United States in Literature. Glenview, Illinois: Scott Foresman, 1989.

Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. Prentice Hall Literature: The American Experience. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1989.

Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. New York, 1855. The Walt Whitman Archive. Edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. http://www.whitmanarchive.org/published/LG/1855/whole.html.